Another Way to Look at Decompression

Challenge your preconceptions and read on with an open mind!

By Steve Lewis

(Excerpted from “The Six Skills and Other Discussions”, Techdiver Publishing, 2011)

Philosophers have argued for centuries about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, but materialists have always known it depends on whether they are jitterbugging or dancing cheek to cheek.

Thomas Eugene Robbins, American Post-Modern Author and Essayist, July 22, 1932

The message to those of us who have opted to engage in scuba diving, especially staged decompression diving in whatever form and flavor, is that we must accept that we are human lab rats engaged in a huge open-source experiment, and that it might be wise to take notes because somebody really should be keeping track of what’s happening to us.

The odd thing about decompression is that what works one day may not work a week later, and what works for you may leave me bent like a pretzel. Furthermore, a practice or behavior adopted and sanctioned by today’s experts may in fact be based on science as shaky as the addled ravings of a sixteenth-century alchemist and by next month be exposed as abject stupidity.

In practice, decompression can also appear to defy everyday logic. For example, if a set of dive tables suggests a diver stops his ascent at nine metres (30 feet) on his way to the surface, making arbitrary extra stops deeper in the water column in a bid to “add conservatism” can in reality do the opposite and cause him serious additional decompression stress.

In short, decompression is a crap shoot2 and in the experience of many who conduct this type of recreational dive, getting it right involves a certain level of wet-finger-in-the-wind estimation and the offering of silent prayers.

But there is some help available. For instance, there is a growing body of data about successful and unsuccessful technical dives collected and available for study thanks to a growing body of technical divers. Admittedly, these data are a statistician’s nightmare because of the wobbly methods used to collect them, but they have helped to inform a sort of best-guess behavior when it comes time to plan a staged decompression dive. Few of these practices are founded on real science or follow any rigorous third-party scrutiny, but they seem to work reasonably well for the vast majority of those of us who engage in diving to “great depths for a long time.”

With that in mind, l would like to share with you a few of those best-guess, seat-of-the-pants practices that relate to decompression planning, specifically something called variously Deco on the Fly or Contingency Decompression or Controlled Ascent Behavior. I believe that understanding this and the thinking behind it may help stack the odds in a dive team’s favor whenever a decompression dive is planned, especially in the event that something goes wrong during that dive and the carefully crafted plans are ripped up by Murphy.

A DAY LABORER’S PRIMER ON DECOMPRESSION THEORY

You may be a seasoned pro with a bunch of tech dives behind you, an experienced sport diver who is curious about tech diving or a rank novice who has just wrapped up open water certification; in a few cases, you may never have done a single dive and are just curious to find out if diving is your cup of tea. Whatever the case, let’s take a few minutes to do a short, what’s-what and who’s-who of decompression theory and its practical application. 3

Since John Scott Haldane’s first iteration of a dive table, built a little more than a hundred years ago on intuition, self-experiment and input from several farmyard animals and Royal Navy ratings, an assorted collection of interested parties have been researching the perfect decompression model. The list of participants includes military personnel, physicists, assorted medical doctors including several anesthesiologists and hyperbaric specialists, mathematics majors, at least one helicopter bush pilot, several computer programmers, a handful of statisticians, and one or two lay people. As a result the average diver is spoiled for choice, and there are decompression models of many shapes and sizes on the market. Surprisingly, the majority work, and for the simple tasks asked of them by most divers around the world, each of them is serviceable to some degree or another.

Almost all the decompression tables available to the rank and file recreational diver are based on a simple mathematical construct that tries to model the physiological effects of breathing compressed gas at depth and then ascending back to the world of one solitary atmosphere4. Essentially most of the decompression algorithms in general use by the tech diving community attempt to track inert gas uptake and off-gassing in a diver’s body relative to variations in gas density, ambient pressure and time using rather simple mathematics. (If you are thinking this sounds like a job for Differential Calculus Man, come up to the front of the room and help yourself to a Marvel Comic).

In the 100 years or so that these things have been evolving, there have been many major forks in the road to decompression Happy Land. The work of Professor Albert Bühlmann, Max Hahn, David Yount, Eric Maiken, Erik Baker, Bruce Weinke, Anders Ersson, et al is thought-provoking, sometimes contentious, and above all gives armchair decompression theorists fodder for the technical diving community’s analogue of a university faculty cocktail party debate. The acolytes for each side can argue gas kinetics, dual phase vs. dissolved gas models, the role of inflammatory response to hyperbaric trauma in multi-day deco diving, the efficacy of deep stops, and a whole bunch more theoretical stuff among themselves until their dates pass out from sheer boredom… all of which is beyond the scope of this article.

I want us to consider instead the suggestion that when we stand back and look at the collective outcomes of all the various algorithms and theories, tables and schedules we have to choose from, there is common ground among them. In fact, if we were to get a collection of decompression schedules for the same dive from a handful of different decompression models and compare them side-by-side, we might notice that each has a particular shape to it. If we traced a graph tracking depth over time, the curve of each schedule would be slightly different but each would follow a similar shape: a variety of flat parabolic curve.

What, then, if we were to learn the shape that curve makes? Could that help us to understand decompression better? Would we be able to execute seemingly complex ascents from deep trimix dives more fluidly and with more fluency if we understood the mechanism that dictates the shape of that curve?

I think we can, and I believe that learning the shape of a decompression curve is a simple and abundantly useful exercise. I’ve heard this technique called Deco on the Fly, Ratio Deco, Seat of the Pants Deco, Pie Deco, and Contingency Deco. All attempt to do the same thing, which is to build an ascent strategy that will mimic one drawn out ‘longhand’ with the help of decompression software or hard tables.

Just to be clear, I am not suggesting that this technique — let’s call it Deco on the Fly — replaces cutting a set of well-defined tables with proprietary decompression software or using one of the ready-made decompression tables available at your local dive store. Rather, that by knowing the trick of Deco on the Fly and how to manage your ascent behavior to fit a regular standard pattern, you will have a tool to help you sense-check the output from your favorite decompression planner. More importantly perhaps, you will also have an ace up your sleeve should you need to win a hand or two when playing cards with Murphy.

Allow me to explain.

THE FIVE WAYPOINTS AND SIMPLE ASCENT BEHAVIOR

At first glance from a diver used to making nothing more than three- or five-minute safety stops on her way back to the surface, a full decompression schedule can look confusing and terribly complicated, especially when the first stop called for is deeper than the sanctioned sport diving limit.

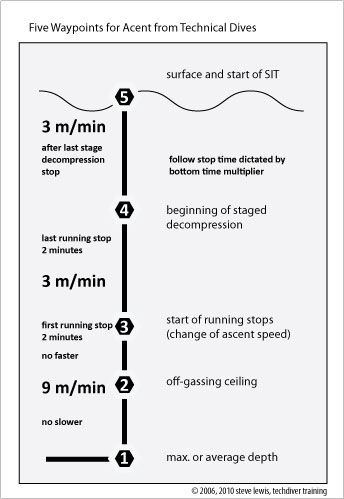

Regardless of how complicated an ascent looks, the journey from a dive’s maximum depth (or average depth) to the surface can be broken into bite-sized segments. This goes for ALL recreational dives whether they take place in 100 feet or 100 metres. The secret lies in first identifying five fundamental waypoints that all dives share:5

- 1Planned Maximum Depth or Actual Average Depth

- Off-Gassing Ceiling

- First Running Stop

- Staged Decompression Stop(s)

- Surface and Surface Interval Time (an often neglected but important part of all staged decompression dives)

The diver’s behavior between these waypoints conforms to another set of fixed values that works for all dives. It is that the diver ascends at nine metres or 30 feet per minute but no slower, between waypoints one and two, and nine metres or 30 feet per minute but no faster between waypoints two and three. The diver then moves at three metres or 10 feet per minute between three and four, and once the last stop is completed (usually at either six metres or three metres – that’s 10 or 20 feet), he will go slowly to the surface no faster than three metres or ten feet per minute.

That seems easy enough, so let’s add one small refinement to make it more applicable to technical diving.

Running stops6 are a series of brief stops that characterize ascent schedules typical of decompression profiles kicked out by dual-phase algorithms. For our purposes, the first stop and the last stop in the series should each be two minutes. The remainder need to be one minute stops. This effectively is the same as saying the diver moves between waypoints three and four at three metres per minute, with a one minute stop at the first running stop and the last. Either way, the transit time between the two waypoints will add up to the same number of minutes.

Now waypoint four – staged decompression stops – is the only other thing to look at more closely. Everything up to this point is essentially the same regardless of the dive’s profile. That is to say that every dive has a maximum or average depth, an off-gassing ceiling, running stops (or at least a portion of the ascent where the diver should slow down from nine metres a minute to three a minute), and a surface interval. Whereas sport dives have a single, simple safety stop, the dives we are discussing have at least one, and probably more, staged decompression stops intended to allow some time for the excess gas(es) in the diver’s body to be expelled during the normal breathing cycle. Waypoint four is something that varies from dive to dive, and we can use Deco on the Fly to work it out.

WAYPOINT FOUR: DECOMPRESSION STOPS

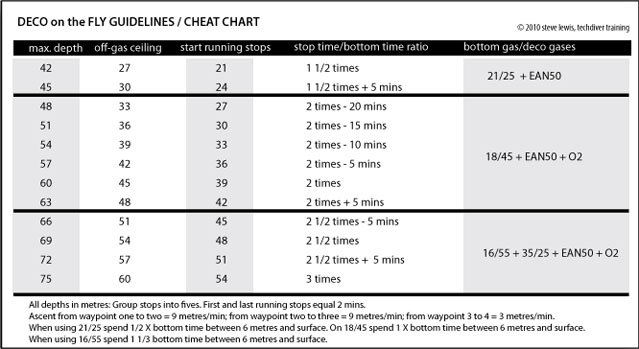

When we want to create an ascent schedule based on Deco on the Fly principals there are a few simple ‘guidelines’ we must work within:

- Remove as many variables as possible (standard ascent behavior, standard gases)

- This system works for dives between 42 metres and 75 metres

- The off-gassing ceiling is 1.5 bar (one and a half atmospheres, 15 metres or approximately 50 feet) shallower than the max depth

- Running stops can start immediately above or up to 10 metres above the off-gassing ceiling7

- Running stops are one or two minutes long and the maximum number of running stops is five

- Gas switches must be made according to the schedule. If a gas switch is off-schedule, reset the clock starting at the point where EACH team member is on the “new” gas

- Spend at least four minutes at the depth where gas switches are done. Follow the normal shape of the curve at the next stop

- A staged decompression stop’s duration is a minimum of three minutes

- Decompression stops are part of a short series that conforms to a simple mathematical pattern that is unique for each gas

- Each series consists of blocks of five numbers that fit within the operational limits of a decompression gas and consists of five evenly spaced stops, the total duration of which adds up to a specific ratio of the total bottom time

- Patterns or Curves repeat through the range of each decompression gas used during ascent

- A close fit works; do not fret details as long as the total time spent completing each series of stops adds up to the required value

- Take notes. Always track what works for you. Deco on the Fly is a guideline and there is nothing sacrosanct about it. Where there is a degree of latitude, write down what worked and if you have to do it again, follow a similar approach.

The reasons for explaining the concepts behind this are simply to open your minds up to different ways of looking at dive planning and dive execution. I dive with tables output by V-planner for my personal dives. Deco on the Fly is my fall-back plan and the concepts behind it merely help me to understand what those V-planner schedules are telling me. Deco on the Fly helps me to control my ascent behavior and, I believe in conjunction with all the other best practices such as hydration and rest, helps me to maintain a 100 percent success rate pulling off decompression dives without incident. I can make no predictions or recommendations regarding how it might work for you. None. The truth is that Deco on the Fly may put you in a similar position to a store-bought guinea-pig being taken to a Peruvian BBQ. Please be warned.

In closing, let’s review a few points that relate to decompression planning in general.

- ecompression algorithms are just pure mathematics trying to model biology

- Biology is weird and is difficult to model with pure mathematics

- Decompression theories contain varying amounts of guesswork – some more than others since goats and Jell-O do not supply intellectual feedback

- Given all the above, you realize and accept that by conducting staged decompression dives, you have become part of the experiment. TAKE LAB NOTES!

- Decompression theory is constantly being refined (The only constant is change)

- There is no such thing as a foolproof decompression schedule

- Decompression is affected by several variables: some, like hydration, we can control, and others we cannot.

- Whenever you exit the water after a staged decompression dive – and regardless of what your decompression schedule or (gods forbid) your computer is telling you – LISTEN to what your BODY is TELLING YOU.

- Given a few basic rules and some simple “memory work” almost anyone can produce a decompression schedule on the fly that’ll work… sometimes.

So now that your curiosity and desire to know more has been peaked… please visit https://www.tdisdi.com to find a TDI Instructor to meet your particular educational needs. Who knows how “deep” your interest will take you…but not till you have the proper training!

This article was based on and is an excerpt from “The Deco Curve: Controlled Ascent Behavior and Contingency Decompression on the Fly” a chapter from the successful book by Steve Lewis called “the Six Skills and Other Discussions.” This book is available at select dive stores and through onLine stores such as Amazon and Create Space eStore via: https://www.createspace.com/3726246.

1 Decompression stress describes the collective issues of Decompression Illness, Decompression Sickness, and perhaps most importantly, sub-clinical bends and bubble problems.

2 The phrase: “Decompression is a crap shoot!” is a phrase attributed to Bill Hamilton and John Crea when, as experts on decompression theory, they made a presentation to an early assembly of tech diving enthusiasts

3 For a much more definitive study of this topic, I suggest adding Deco for Divers: Decompression Theory and Physiology by Mark Powell and Deeper into Diving by John Lippermann and Simon Mitchell to your personal library and reading both from cover to cover.

4 The notable exceptions are models based on statistical analysis of risk and known collectively as probabilistic tables. The math used to predict a diver’s outcome from a specific dive does not attempt to model gas kinetics but instead present those who use them the option to conform to dive profiles that have an estimated degree of risk of DCS based on the outcome of similar dives.

5 These waypoints and basic ascent behavior were first introduced in Chapter Four.

6 Christened deep stops when the concept was introduced to modify old Haldanian style “bend ’em and mend ’em” ascent schedules

7 For examples here, I have used six metres (about 20 feet) for the interval between waypoints two and three. This helps to produce schedules that correspond closely with decompression curves from V-Planner software (a VPM-B algorithm) set at +3 or +4 conservative level.

Before we get into that review, we thought it might be helpful for you to understand why some rebreathers are not on our list. This is by no means a reflection on any rebreather manufacturer. TDI selects rebreathers based on a few things: production of units, user manual and third party testing. That is just a short list of some of the criteria. We have also never authorized the training on “modified” or “homebuilt” units; why is this? For two of the reasons just listed: there would be no user manual to explain how the unit would work with the modifications or as a home build, and there would be no third party testing. The end goal in everything we do including approving rebreathers is diver safety.

Before we get into that review, we thought it might be helpful for you to understand why some rebreathers are not on our list. This is by no means a reflection on any rebreather manufacturer. TDI selects rebreathers based on a few things: production of units, user manual and third party testing. That is just a short list of some of the criteria. We have also never authorized the training on “modified” or “homebuilt” units; why is this? For two of the reasons just listed: there would be no user manual to explain how the unit would work with the modifications or as a home build, and there would be no third party testing. The end goal in everything we do including approving rebreathers is diver safety.

Cave training is also a progression in training starting with caverns where you learn the basic techniques for deploying guidelines, buddy communication with lights and air management, all while staying in the ambient light zone. The next course is cave which takes you beyond the ambient light zone further into the cave requiring more air management skills and guideline techniques. The pinnacle of cave training is full cave; here you will learn complex circuits with jumps off the mainline and even more air management to allow for decompression dives. Please note: Decompression procedures is a pre-requisite for this course, decompression diving is not taught as part of the full cave course.

Cave training is also a progression in training starting with caverns where you learn the basic techniques for deploying guidelines, buddy communication with lights and air management, all while staying in the ambient light zone. The next course is cave which takes you beyond the ambient light zone further into the cave requiring more air management skills and guideline techniques. The pinnacle of cave training is full cave; here you will learn complex circuits with jumps off the mainline and even more air management to allow for decompression dives. Please note: Decompression procedures is a pre-requisite for this course, decompression diving is not taught as part of the full cave course.

To: All current Prism Instructors and Instructor Trainers:

To: All current Prism Instructors and Instructor Trainers:

Many years ago this new breathing gas was introduced to the diving industry, and its name was Nitrox. Many divers then and now continue to use and get trained to use it as their primary breathing gas, and there is a long list of reasons why. At the top of that list are: decreased uptake of nitrogen, reduced post-dive fatigue and most importantly, when used properly, increased safety margins. Nitrox has other benefits as well; the basic nitrox course is not your stopping point when it comes to its uses.

Many years ago this new breathing gas was introduced to the diving industry, and its name was Nitrox. Many divers then and now continue to use and get trained to use it as their primary breathing gas, and there is a long list of reasons why. At the top of that list are: decreased uptake of nitrogen, reduced post-dive fatigue and most importantly, when used properly, increased safety margins. Nitrox has other benefits as well; the basic nitrox course is not your stopping point when it comes to its uses.

Traveling with your CCR (Part 2)

Traveling with your CCR (Part 2)

Planning your Dive Related Activities for months ahead… on an Expedition or at home!

Planning your Dive Related Activities for months ahead… on an Expedition or at home!