He saw combat in Vietnam as a battlfield medic and heroically risked his own life to render aid to his fellow soldiers. In spite of repeated exposure to artillery, mortar and rifle fire he emerged unscathed after a year “in country.” »

He then put in nearly 20 years as a commercial diver and later came within minutes of being trapped under the World Trade Center towers on September 11, 2001. He lost his car, clothes and wallet when the attacks occurred just as he was gearing up to dive beneath the area on a diving job. He escaped on foot in his wet suit. His cell phone was found in the debris by a fireman who used it to help coordinate rescue efforts. Meanwhile, Chatterton was picked up by a rescue boat that took him to New Jersey desperately hoping to get word to his wife that he had survived. His passion for shipwrecks and their exploration diverted him from his full time vocation as a commercial diver in the late 1980s. Without fanfare, John established himself as one of the real purists in the north Atlantic wreck diving community as he took part in expeditions to the Andrea Doria and scores of other wreck sites in the region. But it was a chance trip to scout a rumored wreck located 60 miles off the Jersey coast in 1991 that forever altered his life.

WWII U-869

Chatterton was the first diver to ever lay eyes on an unidentified German U-boat from WWII that had lain undisturbed and undiscovered for nearly 50 years entombed on the silty bottom at 230 feet. This began a six-year commitment to determine the wreck’s history and identity. Famously known simply as the “U-Who” since all naval archives had no record of any submarine, from any navy, being where it was… Chatterton and dive partner Richie Kohler set out to prove the U-boat’s provenance and honor her war dead still contained in her dark hulk. The quest tested their mettle in many ways as rival wreck diving groups attacked with vicious (and undeserved) criticism and attempted to run interference. Meanwhile the wreck itself proved an unforgiving and claustrophobic environment that seemed to defy all attempts to conquer… and ultimately claimed the lives of three fellow divers.

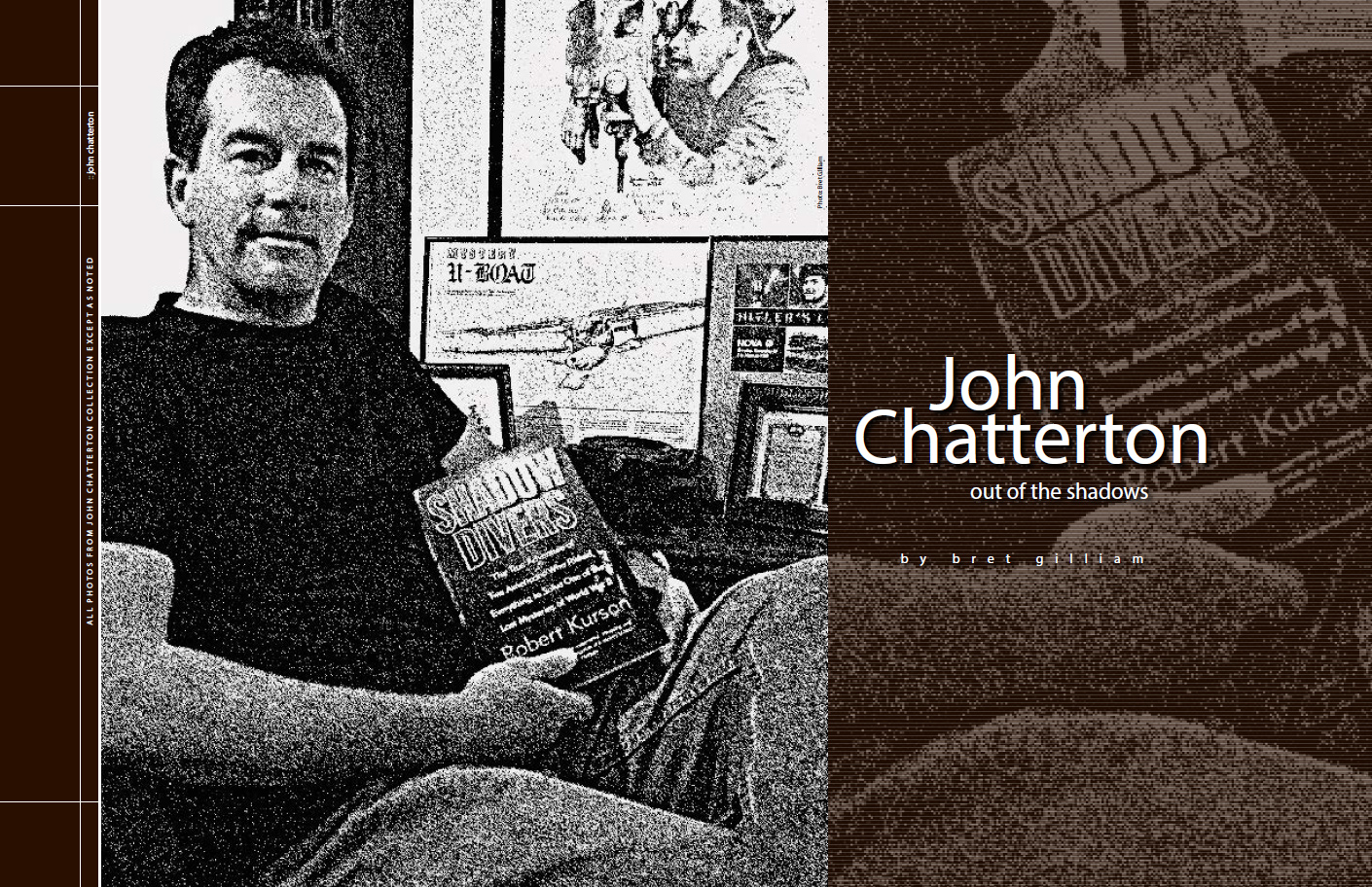

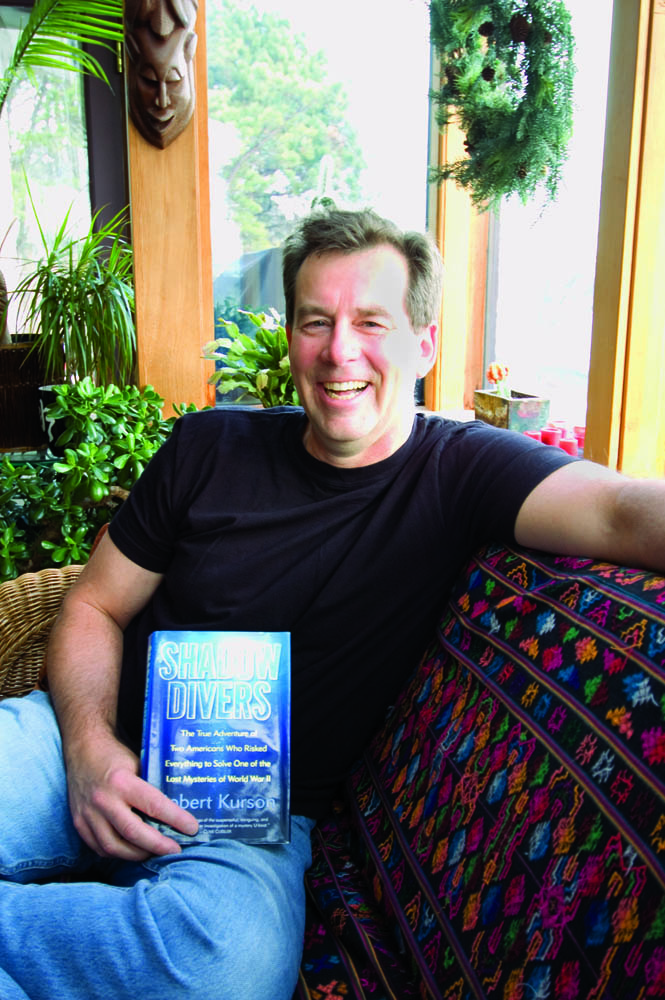

Although a lot of Chatterton’s pioneering wreck dives had been chronicled in various books and magazine articles within the diving industry, ironically it was a non-diving, unpublished author from Harvard named Rob Kurson who finally got his story straight in the runaway best seller Shadow Divers released to both critical and commercial success in 2004. Kurson’s gripping account of Chatterton and Kohler’s exploits in pursuit of the U-869 attracted a mainstream audience that was fascinated by the story of two men’s lives that became intertwined in a naval detective thriller that read with the pace of Clive Cussler novel. But the non-fiction tale of deep wreck exploration, tragedy, sacrifice, and final fulfillment captured the imagination of nearly a million readers and set the stage for a major Hollywood movie to be adapted from the book. Production is scheduled to begin in 2007 with a major studio behind the project, an award winning director, and speculation about which A-list actors will be cast to play Chatterton and Kohler. With the first proceeds of his royalty stream, Chatterton uprooted himself from New Jersey and planted new roots in Maine. I caught up with my new neighbor and old friend who now lived just across Casco Bay from my own island home.

We’re sitting in your waterfront home in Harpswell, Maine, which cracks me up because it’s the first interview that hasn’t required me to get on a plane and travel. I discovered Maine ahead of you, what brought you up this way? I thought you were a Jersey boy?»My wife Carla and I were living at the Jersey shore, but we were living on the impoverished land side, not the Atlantic side of the street. We decided that we wanted to live by the water, and we wanted to kind of get away from traffic, from rush hour, that sort of thing. So you moved to Maine to get away from all the urban stuff that drives everyone insane, but had you ever been here before?»We had friends here in business, the Lone-Wolf documentary film group in South Portland. We visited and we fell in love with the place like you did. We had to move.

Maine has become almost an outpost of a lot of diving professionals. You moved here, I came back in 1991, Stan Waterman has been living here since his dad bought a place in Sargentville around the turn of the century. Bill Curtsinger, one of National Geographic’s long time underwater photographers, has been here for years. Chris Newbert moved just across the border in New Hampshire from Colorado, and Mauricio Handler, who’s a wonderfully talented photographer from the British Virgin Islands, relocated to Brunswick, right up the road here just this last year. So it’s actually become an interesting enclave of divers that have come here and set up shop.»Maine’s way of life is something that certain people embrace. Maybe that’s the appeal to divers. Divers are so much interested in going their own way, being rugged individualists and that sort of thing, they are less inclined to follow. Yeah, the lemmings aren’t falling off the cliff here very often, that’s for sure. Let’s go back a bit. You grew up in Long Island, where did diving come in?»As a kid, I lived at the beach. I was always surfing, snorkeling, diving, spear fishing, that kind of thing. I think I made my first scuba dive with some neighbors. I was ten years old, they made an aluminum tank with no weight, and I just kind of floated around on the surface. I quite literally remember looking down into the water and seeing the light rays penetrating down into the water and thinking “What’s down there?” Diving was a sport for me that became a vocation. I guess I got sucked in.

After high school you volunteered for the army as a medic, saw combat duty in Vietnam, and got honorably discharged after four years. What next?»I went to Florida got a job at the local hospital down there working as an arterial blood pulmonary function technician. But I felt like I wanted to do a little bit more, I wasn’t sure exactly what that was, and I moved up to New Jersey. And now I’m a guy with a background in construction, commercial fishing, and respiratory therapy, and I came to the conclusion – almost through an epiphany – that the best course of action for me was to become a commercial diver.

Construction Underwater

Where did you go to pick up this training?»I went to trade school in Camden, New Jersey, The Divers Academy of the Eastern Seaboard. It’s still there. Most of the graduates from commercial diving schools end up going out to the oil patch where most of the work for commercial divers is. But I was going to be much happier working in the underwater construction business as opposed to taking off for the gulf. I was working on dams, bridges, bulkheads, pipeline jobs, all kinds of things, and I remember the first time I put a helmet on and got in the water. My breakout dive was working for a power plant for Con-Edison in NYC on the 11-7 shift.

Trying not to get sucked into the intake?»Yeah. Well, they are memorable dives, and that was certainly 1. John at home in Harpswell, Maine 2. On a commercial dive, 1991 3. On dive work barge with World Trade Center in background, 2001 one of them. You’ve got all this phosphorescence in the water, and you have the hum and vibration of machinery all through the plant. It’s not an easy job but I kept at it for over 20 years. You start out low, but very quickly I became a diver, and then I was a foreman, a supervisor, and that sort of thing. I enjoyed the work. I liked putting a hard hat on and getting down in the water and figuring out how to get the job done. There were very few downsides.

You began to have some interest in sport diving, motivated by an interest in wrecks.»Well, commercial work slowed down. And I thought what I’d like to do is get in the water and do some fun dives. Some light and easy scuba dives, just to keep my head in it; to keep on top of it as a professional diver. That was in 1982.

You and I came from similar backgrounds… exmilitary, ex-commercial, so we were exposed to technologies, methodologies that really were completely beyond the average diver. Did you find a conflict there when all of a sudden you’ve got guys working in deep, dark, cold water, and thinking there might be a better way of doing this?»I was interested in wreck diving. The thing that really appealed to me was the complexity of it. When I put a hard hat on, I knew I had my job, and the guys in support have theirs. Everyone’s working together. It doesn’t matter if it’s your tender, or the guy on the crane, or the guy working communications, or the other divers, everybody had a job. Not on scuba. On a shipwreck, you’re not part of the machine, you are the machine. Everything comes down to your responsibility. It’s physically challenging, just to be capable of carrying the equipment. You’re in cold water, you’re in deep water, and you need to maintain a physical fitness level that will carry you through when things go bad. At the same time, there’s the intellectual aspect. It’s not just about understanding diving. A lot of that was what I brought in from commercial diving, studying dive physiology and technology, making your own dive tables, and all that kind of thing. You also want to understand shipwrecks and what it is that you’re looking at. You’re talking about maritime history in its entirety. So you’ve got something that is physically demanding, intellectually challenging, and you have to add to psychological stress. You find yourself in intimidating situations. You need a certain degree of mental toughness. You really need to develop the determination to bring all this together. When I looked at wreck diving, I was totally enamored with the complexity of the activity.

Andrea Doria and the Mud Hole

What wrecks were you regularly visiting?»For me, it centered in two places. The Andrea Doria and the Mud Hole in New York, a place that really only got about 200 feet deep. But you are talking about extremely difficult dives. You were in visibility that may be as little as one foot. You’re trying to work off a bottom that is extremely silty, confusing just because of the orientation of the wrecks itself, and you’re talking about fishing nets all over the place. There was even one wreck where the mast was still intact and there was a fishing net draped across it. A friend of mine got disoriented in 190 feet of water, decides to blow back to the surface. Blows right into the fishing net, and stops. It was an environment about as intimidating as it can get. We used to say we would go to the Andrea Doria to tune up for diving in the Mud Hole. Conversely, when you were picking up a lot of dives in the Mud Hole, by the time you got to the Andrea Doria, you were ready to go. The Doria wasn’t so much the depth, wasn’t so much the current, wasn’t so much the cold water or limited visibility – all those were factors, but thing about the Andrea Doria was the vastness of the interior. The Andrea Doria was perfectly willing to give you far more rope than you needed to hang yourself.

In the same era, I had contacts for a long time with guys who were doing really pioneering stuff in cave and deep diving. They were always looking for any innovative way to try to give them the edge to come back. In the late 1980s, when I was exposed to wreck divers in the north Atlantic, it struck me that there was little interest in crossing over the technology that these other divers were using and trying to apply some of that to wreck diving. How did you look at this whole situation? As a commercial diver, you were used to having certain disciplines. How did you feel about guys who were blindly penetrating these wrecks with no comeback protocols?» Philosophically, at the time, there was a world of difference between wreck divers and cave divers. I don’t mean to say there was an antagonist relationship between the two, but cave diving techniques and technology were being developed for the caves. Wreck diving was a different environment. Now, I’m a certified cave diver, and I understand what running lines is all about, but in shipwrecks, the problem with a guideline is sharp edges. It is not a line-friendly environment.

That brings us to the discussion of the practice known as “progressive penetration” which entailed studying blueprints and architecture of these wrecks to try to give you the edge of being able to recognize your whereabouts inside the wreck and find your way back out. Unfortunately, this produced a very mixed safety record.»All of that came from the Andrea Doria because that was a very well documented wreck. There were extensive, detailed deck plans, and the wreck wasn’t very old so you could really identify where you were. But the most important thing was to proceed slowly. That system worked very well for me and most of the divers. But where the system broke down was when divers who came and observed what we were already doing perceived progressive penetration as something akin to “go inside, swim around, but remember the way out!” That is where divers really got themselves in trouble. There were many fatalities associated with those divers on the Andrea Doria – going inside, getting lost, and not being able to find your way back out again.

Eventually we were using lines, but not like they used them in caves. We were running vertical lines on the interior of the wreck, usually very short spaces, maybe 60 or 75 feet of line, something high visibility to denote a particular location of something above. Divers were using strobe lights inside, regular lights to hand carry, bringing other divers to leave them staggered along a particularly deep penetration. By the early 1990s, there was a lot more to technique, especially relating to progressive penetration.

Thinking Outside of the Box

I remember speaking about technical diving at one of the dive shows in 1991, when I happened to suggest that the wreck diving community – which was getting bolder and moving deeper – might want to consider stopping by the main exhibits and checking out the reels that the cave divers use. I suggested that these reels might provide the safety edge when you’re inside a wreck that’s on its side and suffering some breakdown from age, and all of a sudden silts up and you can’t see, maybe that would bring you back out. And I remember that a particularly vocal guy in the back basically shouted me down and told me to mind my own business and not tell the wreck divers how to do things. I found it interesting when I came back to speak the next year and someone came up to me and said, “Remember that guy that was giving you so much crap about the penetration reels?” And I said, “Yeah. I apologize, maybe I was out of line.” The guy says, “Well, maybe you weren’t, because he got lost inside the Andrea Doria and died.” When did you start to think that maybe we could take some of the technology from caving and commercial diving or even military stuff, and how can we best apply it to make it safe?»

I was grabbing it even in the late 1980s. But what I wasn’t willing to do was take something that I was doing, and hold it up to the world and say, “I have the answers. This is the way to dive these deep shipwrecks.” I fully understood how dangerous these wrecks were and how far out on the limb I was going. I also had a pretty good handle on my abilities. Just as you discovered in your pioneering deep diving work, I did not feel that what I was doing was suitable for everyone. And therefore, the last thing I wanted to do was encourage someone to do something. At this time, there’s no technical diving training, there’s no TDI, there’s no structure out there to certify, to instruct, to educate anybody. The last thing I wanted to do was to offer tidbits of potentially lethal information. I spent more than half my time by myself and I would experiment with things that I felt would give me insight that would be something that I would learn from. But I also understood that the public could misunderstand what I was talking about. So I did not feel that I was in a position to become an educator.

There were too many guys out there that see something to be gained by being the new messiah and at the same time there’s another guy on the next boat with a completely different take on how to do things. And a lot of motivation was centered on bringing stuff up from the wrecks. I don’t know whether it’s financial, or just ego, or what. I’ve brought up some valuable things from shipwrecks, but I don’t think I’ve ever brought up anything illegal. I don’t think I’ve violated laws. I know there are guys who have done the wrong thing for the wrong reasons, for no apparent gain. A lot of crap has come with the “treasure” label, and some of that stuff I don’t get. I don’t understand. One man’s trash is another man’s treasure, I guess.

Technology and Technique

Sheck Exley, the infamous cave explorer who was tragically lost in 1994, once commented to me that some of these North Atlantic wreck divers were risking their lives for stuff that if it was laying by the side of the road as you drove down the highway, you wouldn’t stop your car to pick it up. On the other hand, he admitted that a lot of people couldn’t understand his drive to explore the back end of deep cave systems. But the primary difference was fueled by the approach to technology and technique that seemed to be lacking with the wreck divers.»Well, in many ways he was right. The artifact was the trophy. It wasn’t so much the thing itself, it’s what it represented. What happened on the Andrea Doria was there were people who felt that they needed that recognition. That’s what got these guys into trouble. There wasn’t a lot of long-term perspective and a lot of corners were cut. There should have been more emphasis on experience, technique, equipment methodology. Not all shipwreck divers are mature enough to approach the wreck in that way. They weren’t really about the art, weren’t really about the diving, weren’t really about the wreck, it was about the trophy. They had to have the recognition.

If you take a bit of historical perspective and look at the earlier wreck expeditions, you’ll see Bob Hollis, Peter Gimbel, Jack McKenney, and these guys that were going out on the Doria in 1973. They were such clinicians to a certain degree, they approached it with all the tools they could muster at the time, and then took it one step further by actually going into saturation. Now, all of a sudden in 1991, divers emerged as aggressive in some of their attacks on the Doria, but they’re just so unbelievably less informed that it shook people up a bit.»When you’re starting out that way, I don’t think good things are going to happen. At the same time, there were other people jumping in the water who were interested in the art of wreck diving. They were coming back with some sort of insight into the wreck, into diving, into themselves. But they went humbly, as someone who is going to learn as opposed to someone who’s gonna go there, grab some loot, and pound their chest about how great a diver they are.

On the speaking circuit in the early 1990s, someone introduced me to Gary Gentile. At the time, Gentile was self-publishing a bunch of books: Wreck Diver’s Guide and others in a similar theme. As I read through a lot of this stuff it seemed to me that this guy was very well experienced. But I’ll never forget one day he called me up and asked me a question about managing oxygen exposure. I presumed that I was talking to someone who was fairly switched on to the subject, so I launched off on a twenty-minute dissertation on oxygen toxicity. At the end of what I thought to be a very basic explanation of the topic, there was silence for about ten seconds, then he replied, “I have to tell you something, Bret, I don’t have a clue what you’re talking about.” I said, “Where did I lose you?” He said, “About a minute and a half into it.” At the time, I think Gary was claiming more dives on the Andrea Doria than anyone else, yet he didn’t have a clue about what was going on with oxygen management. He was unable to even work the essential physics equations, yet he was surviving.»Gary is one of the best natural wreck divers I’ve ever seen. Intuitively understanding wrecks, being able to get on a wreck, figure out where you are, go to the place that you want to go, and then find your way back out. He has an exceptional gift in understanding wrecks. At the same time, he really doesn’t have the technical/intellectual side to his personality. But for some guys, their diving is not about that.

It was Pure Sensationalism and Ego

In fact, Gentile published one book shortly after people started being introduced to mixed gas, where his knowledge was so fundamentally flawed that he thought all gasses had a “2” subscript. Since oxygen is O2 and nitrogen is N2, he published a book and listed helium as HE2. I look back now, with 17 years of hindsight from when I first met you, why didn’t you step up to the plate and say, “I come from this other technical commercial background, what are you guys talking about here?”»Gary’s primary goal was not education. His goal was promoting himself as an author; promoting his business. He still does that. He still writes books, he doesn’t have a publisher, he doesn’t have an editor, and he publishes his own books. He does it in a vacuum. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with that, but I never assumed he was the spokesperson for me. In the early days, I was not convinced that what we now know as “technical diving” was suitable for the mainstream.

Point well taken, because what we learned was that the more we opened the door to this closet, the more some people stepped through before they perhaps should have. It was a basic lesson in Darwinism because there were a lot of people that got killed or injured, or had unbelievably narrow escapes, that probably never belonged inside that closet door. I think a lot of people became horribly conflicted about whether we were doing the right thing by trying to disseminate the information that, for a long time, had been sealed up and only communicated in private letters. Now, all of a sudden, there was this thing called the Internet, which was beginning to get off the ground, and it was an ideal place for the deliverance of information. Why did the wreck diving community go in a different path than the cave diving community?»The wreck diving community had much more in the way of rugged individualists. The cave diving community had the ability to somewhat control the caves, to control access to the caves: who gets in, who doesn’t. If you come in and you behave badly, then we’re not going to let you in again. Anybody with a 50hp outboard and a rowboat can get out to a shipwreck, so you don’t have that kind of control to accessing the dive sites. When you look at the individuals who were drawn to this in the early days, the divers were very private about what they were doing relative to what we now know as technical dives and experimentation. It was very much kept within the family, a very small circle of friends. Not the larger wreck diving community. You should tread softly, you go there with all humility, and what happened is some people were moving ahead at light speed with technique, technology and philosophy that were flawed. And they were doing it because they needed to draw a following. It was pure sensationalism and ego.

It Turned out to be Piece History Underwater

At the same time, there was all this other stuff going on. The controversies and the rivalries and, in some cases, the bitterness and acrimony that went on between different boats. I’m thinking now at the unbelievable rifts that developed between Steve Belinda’s group on the Wahoo and Bill Nagle’s group on the Seeker. What caused all that?»There were days when I walked around going, “I don’t like any of them.” It came down to issues about respect and the way they conducted themselves. I think Bill was an incredible diver, and in many ways, he was my mentor from a technical standpoint. When we start talking about the rivalries between Belinda and others, a lot of that is back to this, “I know the way” mentality. New ideas, new concepts, new technology, don’t sit well in that environment.

Now you guys were in pursuit of what you were then simply calling the “U-Who.” The notoriety that’s been achieved by this pioneering search to find the damn thing and then to identify what it was and what navy it belonged to is amazing.»Yeah, it was Bill Nagel’s personal interest in exploring new shipwrecks that led us to it. He traded Loran numbers with a fishing boat captain. They had a wreck offshore; Bill had a little wreck inshore. The fisherman wanted to hang inshore when the weather’s crappy, because it’s good for business. Bill loved the idea of a new shipwreck. This guy said, “I know there’s something out there, I know it’s big, I know you guys dive deep, let’s trade.” At what depth?»About 200 feet, he thought. How did this fishing guy find it?»He was running a trip out to the canyons, and quite literally stumbled upon it. At this time, I think there were only three fishing boat captains who knew about this site. But they had no idea that this was a WWII submarine, and they certainly – at this point – did not know that this could be a U-boat.

Who went out there and dove it the first time?»I crossed out a date on Labor Day weekend in 1991. Bill put five divers on, and I put five divers on it. Our deal was that we were going to go out and try to find the wreck, and if we don’t find it, we keep looking. We made about five passes trying to hook into this thing, but we were having problems with the bottom recorder. One bottom recorder was saying it was up to 260 feet, and the other one said it was around 220. In reality it was about 230 feet, but there was a concern about taking a boatload of guys when we said it looked about 200 feet, and all of a sudden there’s a huge difference between 200 feet and 260 feet on air. So our plan was, once we finally got grappled into the wreck, that I would go down and take a look at the wreck. If it was an old trash barge or something in 250 feet of water, that’s not where we wanted to spend a day or risk the other divers.

So what did you find?»It took me six minutes to get down to the bottom. Literally hand over hand, ripping current. It was a strenuous descent, visibility was about five feet. I’m looking at this wreck and I secure the grapple to keep it from blowing away. I swam up current and saw an angled hatch, very prominent, very much a unique feature. I’m at 230 feet and my mind is racing, and I think I know what this is. I look inside the hatch and I see torpedoes. The hatch is completely blown open.

The Dive that Changed his Life

You know you are looking at a submarine, and you know you’re not looking at a submarine from the 1960s.»At 230 feet on air, you’re kind of stupid. But I know it’s a submarine, it appears to be WWII vintage, WWII speaks U-boat, and I am absolutely astounded and mystified. I believe this is a big dive, and I’m taking a moment to appreciate how fortunate I am. During my deco, I’m working over in my mind what I saw, and knowing the history of the area I thought a German Uboat may have been 150 miles away but there’s nothing nearby, and I was trying to remember the number… I’m kicking all this stuff around in my head when one of the crew members on board, comes down and gives me the “what’s up” sign. I take my slate and write “SUB” and stick it in front of his face. He goes berserk. He goes back up to the boat and tells everybody what it is. Of course at this point, they don’t know how deep it is, they don’t know anything. Totally unbridled enthusiasm. Splash by splash, this parade of divers goes past me on the way down to the wreck. I get back on the boat, and Bill Nagel’s words were, “I hear we did good.”

At this point it’s no secret that Nagel had a serious alcohol problem. Was he still diving then, or was he just essentially being a captain and having the enthusiasm that had always driven him take him out there?»I guess we all have people that we know have problems with alcoholism. Bill’s case was extraordinarily severe. At 43 years old he drank himself to death. In 1991, he still had fantasies of straightening himself out. It hadn’t gotten so bad that he had reached a point of no return. He was a very knowledgeable diver, and he understood that he was not capable of making the dive. At the same time, he felt this was the inspiration he needed to turn his life around. So thought the discovery of the submarine was going to save his life. He wanted to dive it, he wanted to turn his life around. This wreck turned a lot of people’s lives around. How long from the time that this wreck was initially discovered on Labor Day weekend in 1991 did it manage to kill the first diver?»The second trip, two weeks later.

How did it happen?»Everyone on that first trip signed up for the second trip. Everyone on the first trip got at least one dive, some got two. They all understood how deep the wreck was, and they understood the conditions down there. There wasn’t anybody who was not just completely overwhelmed with enthusiasm at the possibilities this wreck offered. So everyone felt they had a shot at identifying the wreck. We had a buddy team with Steve Feldman, an instructor from Manhattan, with Paul Skibinski. These two guys had a lot of experience diving together. Their plan called for thirteen minutes on the bottom. Pretty conservative, by my standards. They get down on the wreck, do some exploration, get their thirteen minutes, and Paul heads up the line. He turns, and sees Steve is not following. So he stops and waits. He notices there are no bubbles coming up so he swims back down, and finds him on the bottom. He turns Steve over and sees he’s wide-eyed and unresponsive. Paul is absolutely shattered. He’s over 200 feet deep, his friend and dive buddy could not be in a more severe predicament, and he has to get him to the surface. He starts hauling him up the anchor line. They get up to the point where they see another pair of divers coming down.

Remember, there’s a strong current. This means anchor line in one hand, diver in the other. You’ve got no hand for your BC, nothing for anything. You are at the limit of your ability. He thinks he’s running out of gas. It was physically and emotionally demanding, it couldn’t have been more stressful. The other divers come down. He grabs the regulator from one and at the same time he lets go of the body. So one stays with Paul while the other one chases the body to the bottom. He’s now at 230 feet in the sand with an unconscious, non-breathing diver, and he’s not even linked to the anchor line. He doesn’t believe there’s anything he can do to help Steve. So he ties a line on him, starts up, and miraculously runs back into the anchor line. He ties off the line he’d fixed to Steve’s head. But when we went down to try to recover the body, all we found at the end of the line was a mask and a snorkel. Feldman’s body was recovered five months later by a commercial fishing vessel. According to their track, they picked up the body at some point greater than a mile away from the wreck. He came up in a net. We spent the rest of that day trying to recover his body. We used up the bottom time of everyone on board who we felt was capable of going down to search. There were guys that were emotionally distraught and you couldn’t ask them to go in the water, and had they volunteered you wouldn’t have wanted them to. The last thing you want is someone else getting hurt or killed trying to recover a body. Later, the diving continued with a different lineup. Not everyone who was on the boat with Feldman wanted to continue. There were guys who gave up diving, there were guys who gave up deep diving, there were guys who gave up diving on that U-boat. And then there were others that wanted to continue.

The Unexpected

I credit the Boston Sea Rovers and the Beneath the Seas guys for sponsoring forums and symposiums that made a real effort to bring these groups together, to put together seminars which talked about the new technologies, and it also was a process where a lot of the leading members of different dive communities got introduced to the public for the first time. Sometimes, that was a sobering experience. Back in 1991, I had spoken at the same program with Rob Palmer who’d come over from England. Exley was up from central Florida, Billy Deans from Key West, Jim Bowden flew up from Mexico. We were all introduced to two guys that quite literally scared us to death. It was Chris Rouse and Chrissy Rouse. They babbled in our faces for about ten minutes and then disappeared. The last thing that Chrissy said to Sheck was, “I want to be just like you, but I’m going to be better than you, and I’m going to go deeper than you, and I’m going to be the next Sheck Exley.” When they walked away, Rob Palmer turned to me and said, “Those guys are going to kill themselves.” And before I ever saw them again, that’s exactly what happened.»

I can understand the reaction of you guys. It was tragic and there were a lot of lessons to be learned. It was the first real public focus on the U-869. In 1992, the Rouses had come out and done some Andrea Doria trips. They were different, they were unique since they came from the cave diving community. In many ways, they were perhaps better suited for diving on the submarine. Bill kind of liked the Rouses; they were outlandish and wild, but he also thought they were reasonably capable without fully understanding everything they were doing.

The Rouses, if nothing else, had a reputation for a bizarre father-son relationship. It was competitive; it was characterized in some ways as immature. Were they good divers?»They seemed to be disciplined; they seemed knowledgeable; and if you pulled out the personality, they were capable. This was Columbus Day weekend 1992, thirteen months after Feldman’s death. This was a two day trip; they had been to the U-boat a couple times previously. Chrissy had a spot he was working inside the sub that had German writing on it. He was convinced that he was going to be the guy to identify the sub, much the same way he spoke to Sheck Exley. He had a very high level of confidence and was very vocal about it. He was going to be the one to identify the U-boat.

What happened?»Chrissy, the son, was running a reel inside the wreck to a location around the galley where he was trying to dig out this artifact that had German writing on it to bring it to the surface. The father was waiting outside. Chrissy apparently undermined some heavier steel components within the wreck trying to extricate this artifact that turned out to be a rubber life raft. He’s trying to pull this thing out, he’s digging around, and the next thing you know a large, heavy piece of wreckage lands on him and pins him. He is essentially buried in the wreck, alone, at the end of a line. His father, Chris, was waiting outside. Chrissy does not show up, and he is not going to surface without Chrissy, so he says to himself “I gotta go get the boy.”

At this point, we have the elder Rouse – the father – with the horrible realization that his son is trapped inside the wreck, the dive is way behind schedule, what happens next?»The added complexity is that both these guys are on air. Father goes in, finds his son, uncovers him, takes the reel, and heads out, but not the way they came in. So the supposition is that as they exited the wreck, they were disoriented as to which direction they were facing. They were only about forty feet from the anchor line. This is significant because they didn’t come up on the anchor line, but free ascending. They had spent more time on the wreck searching for the anchor line. They couldn’t find it, they got to the point where they were over 40 minutes into their bottle time, and they had to surface. At this point, they have a huge decompression obligation and they don’t have enough gas to do it. They’re not coming up on the anchor line or tag line or anything, so this whole scenario is about as bad as it can get before they even leave the bottom. It’s essentially a case of making bad choices, and when things go wrong, you have inadvertently painted yourself into a corner, and that’s exactly what happened here. They brought only one of their four stage bottles with them, they did not mark the anchor line with the strobe light, they ran a line inside the wreck, but they didn’t run it from their start point, the anchor line. So they found themselves lost with no up-line. After another series of attempts to share the one cylinder of nitrox they had dragged up with them, everything went to hell.

If I remember correctly, they ended up on the surface with explosive decompression sickness.»Right. But all of this stuff was compounded by the fact that they were hammered with narcosis and they had to deal with almost unbelievable psychological stress. Chris, with his son not coming out of the wreck, being buried and having to extricate him… and for Chrissy, the fact that he was buried inside this thing for a long time before his father even showed up. So 1. Chris Rouse and son Chrissy 2. One of the Rouses’s scuba tanks, still lying on the wreck after their fateful dive you have this psychological state that is created here, and the straw that breaks the camel’s back is Chrissy breathing off of that nitrox regulator and getting water into the mouthpiece. He bolts for the surface. Chris was not going to let his son go anywhere without him. So he comes up, too. The weather was starting to get shitty. I was looking at the water as the two Rouses popped to the surface in front of us. The immediate realization is that they weren’t on the anchor line, and they were not on the surface according to the schedule they left with us. We knew there was more than likely a serious problem. Now you’re faced with a bad situation because you’re so remotely located offshore, you have to get the guys onboard, and even that is proving difficult.»We’re trying to talk to them to get basic information as we’re throwing them lines and trying to get them to the ladder on the boat. We’re asking if they had a decompression obligation. They indicated they had come directly to the surface and they both looked really scared.

At this point, was any consideration given to trying to adopt some kind of omitted decompression procedure and put them back in?»Yes, but they were not fully responsive, and our policy and procedure has always been if you can talk to someone, you can fix it. But if it’s a psychological problem, you can’t take someone who is desperate to get out of the water, and put them back down for decompression. So now you have to extract them. And that means you have to get the equipment off them and get them up on the deck. You’re trained as a medic and as a commercial diver, and right away you must have known that the prognosis was very, very grim.»I knew it was grim, but I didn’t think it was as bad as it was. We got Chris to the back of the boat. He said, “Take Chrissy first.” The son was right behind him. We put a man on either side of the ladder to help him and he said, “I can’t make my legs work.” We quite literally dragged him up and turned our attention to Chris Sr. He very calmly and specifically said, “I’m not going to make it. Tell Sue I’m sorry.” He slumped unconscious with his face in the water. I jumped in, took his knife, cut him out of his rig, and basically did a fireman’s carry to get him onto the deck.

At this point, the only tools you had out there were oxygen and basic CPR. How quickly, from the time you got both the guys out of the water onto the deck, did it take them to go from being able to have coherent speech to becoming irrational and passing out? Obviously we’re dealing with massive CNS decompression hits here, and it’s going to come on pretty quickly.»Chrissy was young and relatively resilient. He was very verbal, expressing his discomfort, he was almost hallucinatory. With very serious CNS, it mimics a stroke. We were not entirely sure how much of what he had to say was true and accurate and how much was delusion. The key was trying to get him calmed down, on oxygen, and trying to maintain as best we could until we could get him air-lifted out by the Coast Guard. Chris Sr. never did have spontaneous respirations. He had a pulse for maybe a minute. We were doing CPR on him and we had a pharyngeal airway that we put in, but you could feel resistance within his body building up. There were so many gas bubbles in his body that, quite literally, his blood was coagulating as we were trying to do CPR. From the time that we pulled him to the stern, Chris Sr. never had a viable chance. You are faced with what can you do and who can you save, and then you get into an argument with the Coast Guard helicopter during the evacuation?»The Coast Guard swimmer comes down with the rescue basket and said they were going to take the son first. I said, “Take the son. Don’t take the father.” At this point, we had done CPR on Chris for something close to two hours. I was adamant, “The son has a chance. I know this family. If the father could sit up and have one thing to say to you, he’d say, ‘Take my boy.’ Chris is not going to make it. The only chance we have is to get the son treated as fast as possible.” And the time element here is absolutely crucial.»We are as under the gun as you can be and we’ve already kind of resolved on ourselves to the fact that Chris Sr. is not going to make it. We’re still doing CPR, but all of our hopes were really with Chrissy.

So how did you reconcile this triage?»I understand the Coast Guard’s position that Chris is not dead until he’s pronounced dead by a doctor, so we’re doing what is procedure, which is to keep doing CPR. But from a practical standpoint, the father was dead and we should expend no further effort in trying to resuscitate him. We should try to focus our efforts on the son. But that’s not the way the system works. Ultimately, the decision was made that both were to go up in the basket and all of you were left behind. The chopper took off with the Rouses to deliver them to the chamber. This presented other treatment issues: the depth capability of the chamber, not to mention the delay.»And you’re talking about a significant time lapse now, between four or five hours.

Both of the Rouses succumbed and passed away due to the explosive decompression they suffered. You’re left out there on the boat rocking away with your own horrible psychological trauma, and you’re facing a long ride back in. This turned off a lot of guys from going back out to this wreck again.»We were absolutely positively traumatized by the accident. Having a fatality is terrible, but having two fatalities is about as much as anyone can imagine dealing with. Having it be a father and son is worse still. There was also a lot of noise from both the cave diving community and the rival wreck divers. This really caused me, Richie Kohler, and others to question what we were doing. Is deep diving worth these two guys’ lives? At the same time, there’s multiple fatalities on the Doria, there’s the Feldman fatality… it’s a lot. We had been relatively low key, going out and doing the deep thing under the radar. Now we’re not under the radar. We’ve got a big target painted on our backs.

You never really seemed to waver in your own personal interest in trying to determine the identity of this vessel. You guys called it the U-Who. It wasn’t where it was supposed to be, nobody could come up with an explanation for why it was there, it had claimed three people’s lives in a very short time. How long after the Rouse incident did you resume diving it again?»That was the last dive of that year, end of October. We were back out there first thing the next summer. You seemed to react to this with a determination that is almost unfathomable for some outside observers. To think that you dove this first in 1991, and how many years until you identified it?»Six years, almost to the day.

This was a journey not only for you personally, but also for Richie Kohler. You two didn’t get along earlier in your dive careers, Richie dropped out of diving for awhile after the fatalities, then you guys came back in and pursued this common interest. It ended up not only producing an enduring friendship and identifying the wreck through your astounding research, but at some point you were finally able to re-enter the engine room, recover the tag that identified the boat as U-869, and put this matter to bed against everybody that had been telling you that you were wrong. Three people have died, unbelievable amounts of finger pointing has gone on, nasty fighting, wild accusations, and you finally unveil the secret.»

We were focused on what we were doing. Kohler and I weren’t looking over our shoulders to see if anyone was watching. Richie really felt this was the right thing to do, for the sailors who had lost their lives and were lying in anonymous graves. Being a German-American, he felt a certain empathy to the predicament the families were in. You don’t stop doing what it is you intended to do simply because it became difficult. The more difficult it became, the greater our personal resolve..

The Rollercoaster of Emotions

You spent six years of detective work. You’ve gone through an emotional rollercoaster, your first marriage breaks up, your career is changing, there’s a bunch of things going on. In 1997, you unlock the mystery. Now your efforts start to attract some attention.»We had been involved with PBS and NOVA was doing a documentary on the wreck.

Was this Hitler’s Lost Sub?»Yes. And PBS had partners in Germany and the U.K., so while they’re building a two hour program in the United States, they put out a half hour program in Germany to find one of the veterans from the wreck. The documentary comes out in 2000, and it is seen and reported. Someone comes to Rob Kurson and tells him about the story that they have seen in the NOVA documentary.

What attracted him to the story?»I think it was the personalities; he probably was attracted to Richie and me on a very basic level. He went to an agent in New York City, and she made contact with us and asked if we would be willing to talk to him. Why did Kurson think that it needed to go beyond the documentary, and what was your reaction to meeting with an unpublished author who was not a diver? What made you think he could tell your story?»Richie and I had been involved with several attempts at writing a book. In every instance, it just didn’t pan out. They didn’t quite get it. So when we sat down with Rob Kurson, we felt there was some kind of challenge involved. What we were trying to get across was that this submarine had left homeport in WWII with these 57 young boys on a mission that was doomed. They’re in Norway, and they’re watching all these U-boats leave, and none of them are coming back. That was the story that interested us: to die anonymously off the coast of New Jersey. That was what we envisioned as the story, that’s what we spoke to Rob about.

Rob spent all day with us. He brought his pregnant wife, and all of a sudden he said he wanted to leave and start writing. We offered him dinner, and he said no, that he had to write. He’s a nut. He has no social grace. He has no concept of anything other than what he’s focused on. He made his wife drive home because he didn’t want to lose anything in his head. And we’re thinking this guy is out of his mind, but at the same time thinking he was perfect for us. He was not a diver; he still isn’t a diver. I think that’s why the book turned out so well. He had to learn everything about diving from us, and he was in a much better position to then present that information to the reader.

In my case, as both an author and diver, I found that to be true as well. I had read earlier accounts of the Rouse tragedy, and Feldman, and all the other elements that made up the other tragedies like the Doria expeditions. Kurson managed to come in and tell the story so well that I wonder whether anybody could have written it from within the dive community.»The same kind of dedication and focus that we had for our diving, he had for his writing. We understood each other right from the get go. He said, “Trust me. I can make this story a bestseller.” And I believed him.

Didn’t you also have to tell him that he couldn’t go out and dive the wreck himself?»Yeah. You’ll love this. He went to his agent and told her he had to go out and dive the wreck with us. She called us up, “Listen, Rob is talking about diving the wreck. You can’t kill this guy.” We agreed, and when he came to us we told him it was a really bad idea. He said he absolutely couldn’t write the book without diving the wreck. We then told him to go to his local dive shop and get certified thinking that would buy us a little time. That once he realized what diving was all about, he would back off. The obvious reality here is that the wreck had claimed the lives of three guys who were experienced divers with many years of diving behind them, and now he wanted to do it in a couple months. So he went to dive class in Chicago. He had to be the instructor’s worst nightmare. When it comes time for the pool session, Rob eases himself into the pool and dogpaddles a little bit, and the instructor goes, “You can’t swim.” And Rob says, “Yeah, you’re telling me.”

So he asks him what he’s doing, and he explains that he just has to make one dive and then he’s done. Just one dive to this U-boat sixty miles off the coast of New Jersey, 230 feet down, and then he’s done. And the instructor tells him to get the hell out of the pool. So Rob is now a broken man. He’s been thrown out of dive school, and he says that he simply cannot go on writing this book. So we sit down with him and ask him what happened. He explains that if he gets water on his face, he gets all panicky. And Ritchie and I look at each other and just shake our heads. This nut who can’t swim and panics when water gets on his face wants to do a deep technical wreck dive? Yeah, right…

So, let me take a wild guess; you don’t let him dive the wreck?»Come on, Bret, hell no! He’s still a non-diver, a non-swimmer, for that matter. The book became such an elaborate project, because now the whole thing must be brought to life based on the narrative that you and Richie can supply to him. It is a fabulous book, a runaway bestseller. One thing that

You not only secured a movie deal but you originally brought in an A-list director in Ridley Scott.»Actually, FOX and Ridley Scott parted company on this. FOX was adamant that they wanted to shoot this in 2006, but Scott wasn’t available in that time frame, so they went looking for a new director. Now they’ve settled on the great Australian director, Peter Weir. His last film was the epic Russell Crowe movie Master and Commander. He also did Witness with Harrison Ford. He knows how to tell a story. Our meetings with him have gone extremely well. He really gets the story and we all like each other.

From Paper to Big Screen

How you’ve come from book to movie is interesting. Especially when you compare it to Peter Benchley, who was practically eating cat food when he wrote Jaws, and nobody could figure out how that book could possibly be brought to the screen. Peter was the first to admit even he wasn’t sure how it could be done because, as you know, sharks don’t take very good direction. Do you envision a hands-on role when this thing goes into production?»I think Richie and I will be consulting more on the diving end of things. Bill Broyles has written the screenplay; in fact he’s working on the fourth take right now. I saw the second swipe that he took at this, and I have to say it literally made the hair on my neck stand up. I was moved by his script. If nobody screws it up between now and the big screen, it’s going to be huge. Do you have any idea who they might want to cast to play you guys?»They want A-list actors. When I look around at the very talented people they have drawn into this and hear them shooting numbers like a hundred million dollars around, I have the utmost confidence that they will find the right people for the job. Well, I guess it’s safe to say we’re not going to see Paulie Shore or Adam Sandler in the parts.»If we’re lucky! How many copies of Shadow Divers have been sold?»So far, somewhere just south of a million copies in hard bound and paperback.

It’s interesting that divers didn’t make this a bestseller… the public made this a bestseller and it was ultimately because this is a human story so well told.»The credit really belongs on Rob’s plate. I can’t tell you how many people have come up to me and said, “I’m not a diver, I know nothing about diving, but I was moved by that book.” The way that Rob wrote it was for the reader, and that’s the mark of a really good book. People feel like Rob is talking to them. You and I could both read the book and take away completely different things, and that’s why people love it. You guys also parlayed yourselves into television?»While we’re working with Rob Kurson and he’s researching the book, The History Channel comes to us and asks to do a television series about divers and shipwrecks. It’s something nobody is doing. Deep Sea Detectives they want to call it and initially they wanted eight shows. We figure we can squeeze in two shows before they realize we don’t know what the hell we’re doing and fire us. I remember the first day we went to shoot the show, the director of photography asked us what else we had done. We said we had worked on some documentaries. He asked us about dramatic things, and we sort of just sat there. We’re at the dinner table when he finally figures out we’re not actors. He freaks out. But now, we’ve done 57 episodes and we’re putting together candidates for the next slate of shows. They’re seen all over the world. I get mail from friends in the UK and Yucatan saying, “I saw you on TV last night!”

Any other projects on the horizon?»This past summer Richie and I put together a project on the Titanic. We went out, we chartered the Russian support ship Keldysh, took the submersibles, we did the whole thing on our own dime, made our own preparations, and then went to The History Channel and sold it as the executive producers. We’re still working on Deep Sea Detectives, we’re producing specials for The History Channel, we’re still promoting the book. Twentieth Century Fox and the Shadow Divers movie has got us busy and we’re consulting with Paramount Pictures on a dramatic television series. The only thing we don’t see in our futures is unemployment.