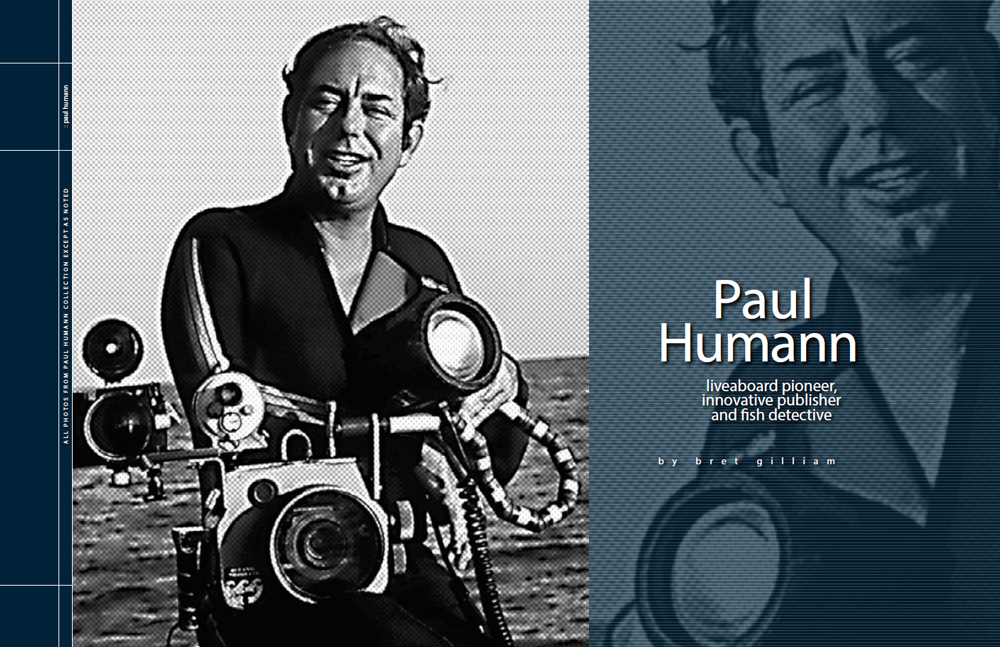

Paul is not just a supremely talented photographer and writer. He’s also an unrestrained truth-teller when it comes to the diving industry’s foibles and often absurdly ill-advised track record of blunders championed by a segment of archconservatives. He was a vocal champion of divers’ rights and one of the first to advocate codifying the practice of solo diving for qualified divers. He also endorsed dive computers, nitrox, applications of technical diving, and enlightened practices for modern liveaboards. At times, his opinions have brought him criticism, condemnation, and harsher reviews from the lunatic conservative fringe. But his vision helped bring all these, initially controversial practices, to the forefront and they are now mainstream.

I like to think of him as a prophet and first-class raconteur who never flinched from speaking his mind and sticking to his principles in spite of the fact that his outspoken wisdom would almost surely have gotten him burned as a witch in an earlier era. Although our paths had crossed many times over the years, the first chance I had to really spend time with Paul was in 1992 when we were both co-hosting a group of divers aboard a liveaboard in the Bahamas. I taught an advanced diver program and he delivered nightly lectures on marine life. We didn’t get one day into the trip before there was an incident. I surfaced from a dive to find the ship’s divemaster/instructor in a total melt-down… pacing the deck, muttering oaths, threatening reprisals. We were off to a good start. I could only imagine that some diver had committed the cardinal sin of not wearing a snorkel or, god forbid, putting his mask on his forehead while waiting to get out of the water.

These were definitely capital offenses in the early 1990s mentality that mandated all divers be treated as manifest idiots… incapable of having a coherent thought about their own diving practices. I gingerly approached the young man in an attempt to discern the source of his angst. He was fresh out of “instructor college” and had a whopping 50-60 dives under his weight belt. But, by god, the kid was a diving professional; it said so right on his fancy diploma framed on the bulkhead. And he knew what divers should be doing and would not tolerate deviations from the ironclad rules posted right next to his diploma. Circling him from a safe distance, I managed to get him to gasp out the transgression that had him so upset. “Mr. Gilliam, I can’t put up with this.

Do you know that Mr. Humann is diving without a buddy? He’s all alone down there. By himself. Solo!” I was shocked and said so… without a trace of revealing sardonic perspective. What would the kid have me do to such a deviant diver? “Well, we just can’t have it. It’s against all safety rules. What happens if he runs out of air? Or has a problem? He’ll die!” I gently explained that the likelihood of Mr. Humann experiencing a problem of any sort that he couldn’t stumble through somehow on his own was pretty unlikely. I mentioned that Mr. Humann had been doing this, professionally, for a while. Like about three decades. With over 8000 dives, most of them solo. And he’d be just fine.

“Oh, no! We can’t be responsible for such bad practices. I’ll have to suspend him from diving,” our hero trumpeted. Meanwhile, the amused other divers and I could look over the rail and observe Paul blissfully absorbed with his camera at a coral head about 40 feet down. He was unaware of the furor he had created. I knew I had to act quickly to head off a scene when he finally surfaced and was confronted by diving’s equivalent of Dudley DoRight in a wet suit. (In all truth, I feared for the kid’s life. Paul was just as likely to snap his neck as listen to a reaming from a neophyte.) I suggested a cunning plan. “Mr. Humann is an old curmudgeon who’s sort of set in his ways.

How about if you be his buddy and don’t tell him? That way, you can look after him.” The kid thought it over and decided that this was an intervention designed by Solomon himself and agreed. Meanwhile, the rest of the divers fled the dive deck, stifling snickers. They knew full well what was to come, I think. The next dive began as Paul gathered his camera gear and slipped over the side to take up residence once again at a favorite coral head. The flash of his strobe confirmed that he was happily immersed once again in his photography and largely oblivious to any outside distractions. Our well-meaning instructor lunged into his own gear and splashed in after him, taking up position about 15 feet behind him. Now all was right again in the diving universe. Wrong!

After about an hour, the kid realized he was running critically low on air. I watched with growing amusement as he desperately tried to stretch his air with breath-holding. A few more frantic glances at his pressure gauge and he was off in a wild scramble of fin strokes and billowing exhaust bubbles. He arrived on the surface about a hundred feet from the boat and then began the “swim of shame” back to the ladder: he had failed to arrive back aboard with at least 750 psi remaining!

He’d also failed to protect the ancient geezer still happily firing away at his fishy subjects. He’d abandoned his buddy. We all gleefully pointed that out. About twenty times. It was a professional failing of biblical proportions. Paul took another 40 minutes or so and calmly swam back to change film. His protector had retreated to the sun deck still mulling over his abdication of duty (and how Mr. Humann could make a tank last so long). In the end, we convinced him to leave Paul alone. Literally. But we suggested that the instructor might want to work on his own self-sufficiency skills and maybe stick closer to the vessel himself where he could be more valuable helping divers out of the water and handling cameras. It was a grim moment in the young instructor’s career. Divers weren’t supposed to behave like this. He’d bring this to the attention of his instructor agency when he got back to port. Paul somehow managed to survive a week of unsupervised solo diving and got a bunch of great photographic images along the way. We never told him about the furor over his diving practices… until now. About seven years later, my company Scuba Diving International (SDI) came out with the first industry training agency program to certify divers in solo diving practices. Of course, the recipient of the first card (#00001) was Paul Humann.

Trying Somehting New

You were born in Nebraska and raised in Kansas, not exactly a breeding ground for divers. What sparked your initial interest?»I was always into water sports… on the swimming team in high school and college, lifeguard, Water Safety Instructor Trainer for the Red Cross, coached the swimming team at Washburn University as a part time job while in law school. Between that and Sea Hunt it was a natural extension of my water sports interests. Okay, I can understand that the Midwest has swimming pools, but what existed for scuba training back then?»Nothing, other than driving to Missouri to dive in abandoned pit mines with surprisingly clear water or in murky lakes.

Where was your first dive?»In 1961 a college friend, who was a diver, and I took a summer vacation to the Keys. My first dive was solo, because being poor college students we only had enough money to rent one regulator. Outfitted with only a mask, fins, snorkel, tank with K-valve and regulator, my friend gave me “comprehensive” dive instructions: “Breathe normal, don’t hold your breath, and when it starts to suck hard – come up!” That first solo dive, which lasted 45 minutes before “sucking hard,” changed my life. I was so enamored by the marine life and beauty of the reef that diving immediately became an all-consuming passion.

What were the Keys like then?»Live coral and marine life was abundant. You could still see large groupers even a Jewfish. Whoops, in the new world of political correctness, I meant Goliath grouper. That first dive was off Sombrero Light, and I remember the wonderful lush gardens of Elkhorn Coral. The area around Sombrero is today nothing more than a pile of rocks. However, before I get the Key’s operators mad at me, let me interject that in my opinion Key’s diving is still some of the best around. Although much of the coral cover is gone, marine life and particularly non-game fish are abundant. I don’t know anyplace in the western tropical Atlantic where you can go see schools of grunts even remotely as large as those in the Keys – I mean grunts as far at the eye can see! I still love diving in the Keys.

Getting Published and Certified

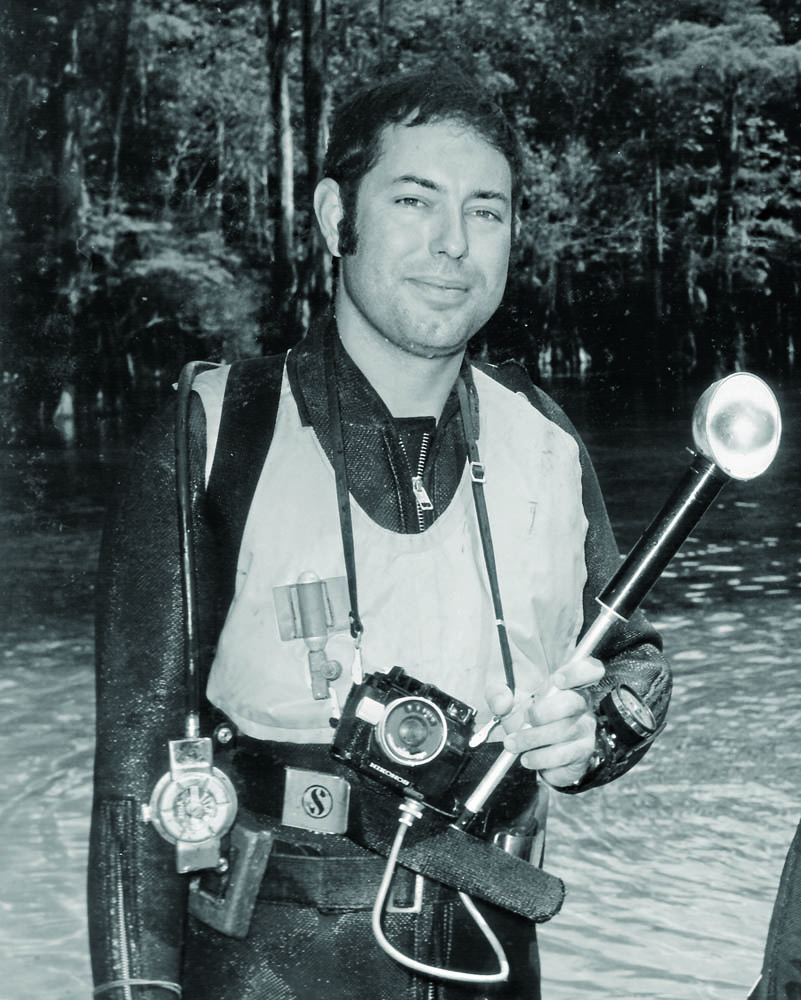

So like many enthusiasts of the era, there was a significant gap between first trying scuba and actually getting certified. When did you get “legal”? And that led to interests in becoming an instructor?»Managing not to kill myself diving for five years, I was certified by a YMCA pool course in 1966. I went on in 1968 to become an instructor for the Underwater Society of America’s Mid-West Dive Council and, as such, automatically became one of PADI’s early instructors, certification #2222.

Share some memories of first getting published?» About 10 of my friends and I formed a diving club named Martini’s Outlaws. The name came from our enjoyment of deep diving – remember the old diving “Martini’s Law” that was taught to divers in those days? It stated: “Every 50 feet you go down is like drinking one martini on an empty stomach.” It was supposedly a way to approximate the effects of nitrogen narcosis. We broke that law a lot. And the fact we also liked martinis didn’t hurt either. Anyway, back to your question, Martini’s Outlaws put on the first mid-west underwater film festival ever in 1969 and one of the guest speakers was Jack McKenney, then editor of Skin Diver and one of the diving world’s foremost photographers (Paul Tzimoulis was the publisher). I showed him some of my pictures and he offered to start publishing me in the magazine. And that’s how it all started. Who were your diving heroes then?»Well, of course, Jack McKenney. Also Dewey Bergman and Al Giddings, who filmed some of the first shark adventures in Tahiti, and Stan Waterman .

Your path to professional diving was a bit more circuitous than some others. You had an established law career as an attorney in Kansas, how did you decide to take “the road less traveled by”?»One winter day while watching the snowfall and wishing I was diving, I simply said to myself “What the hell are you doing with your life?” I knew I eventually wanted to

vessel in Cozumel, had it outfitted with tanks and a portable compressor, and sailed to then remote Chinchorro Banks to dive for a week. Although this was a very Spartan adventure, I thought “Now this is the way to go diving – jump in the water anytime you want and be remote enough you didn’t have to put up with swarms of other divers.” And, that’s the way the idea of a liveaboard dive boat was born for me.

Liveaboards

What were the origins of the Cayman Diver?»I was in San Francisco, on law business, and had lunch with Dewey Bergman, founder of See & Sea Travel and his new associate, Carl Roessler. I told them of my idea and Dewey tells me that Bob Soto in Cayman had the perfect boat for sale. And in fact, Bob bought it with the same idea in mind and actually used the boat for a few trips to Little Cayman, but decided it did not fit into his day-boat operation and wanted to sell it. Next thing I knew I was on an airplane to Cayman and gave Bob a small deposit check. I came home and begged friends, family and, in particular, a wealthy oilman/client for money. I guess my persuasive powers as an attorney were good – because I sold them on the idea – and borrowed with no collateral!

How would you describe its accommodations compared to today’s liveaboards?»Spartan! We had a bunkroom for six, three tiny doubles, two heads and one COLD WATER shower. My motto was “Give them the best diving in the Caribbean, the best food, and the best service, and they will ignore the accommodations.” Apparently I was right because it worked for eight years. What other liveaboards were operating anywhere then?»Well, I started the Cayman Diver in 1972. The first liveaboard was in Australia, can’t remember the name, it has started a couple of years earlier. To my knowledge that was it. Your own Virgin Diver started service with See & Sea a few years later. Those were the only two in the entire Caribbean. How did you market this new concept?»Through See & Sea Travel Service, then owned by Dewey with Carl intending to ultimately buy him out.

Moving up the Ladder

To meet the cravings of your guests, you began a series of slide shows presented in the evenings aboard the Cayman Diver. When did you think that this could be a niche business model itself?»Yes, early on I started giving marine life identification programs in the evenings for guests and they were a big hit. I learned that divers thirst for knowledge about what they are seeing. Then about 1977, I realized that just taking beautiful underwater pictures and selling to magazines wasn’t going to catch it. Although the idea for guidebooks was not fully developed, I still thought it would be important to have a comprehensive stock library of marine species. I made a vow to photograph, in a pleasing way, EVERY fish and EVERY marine invertebrate that existed in the Cayman Islands. I came close to achieving that goal before leaving Cayman in 1980. That library of images became invaluable later as the guidebooks idea evolved.

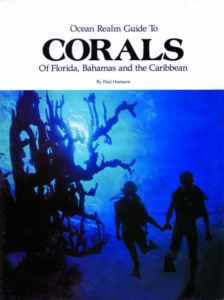

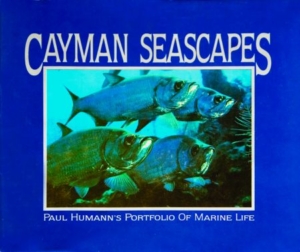

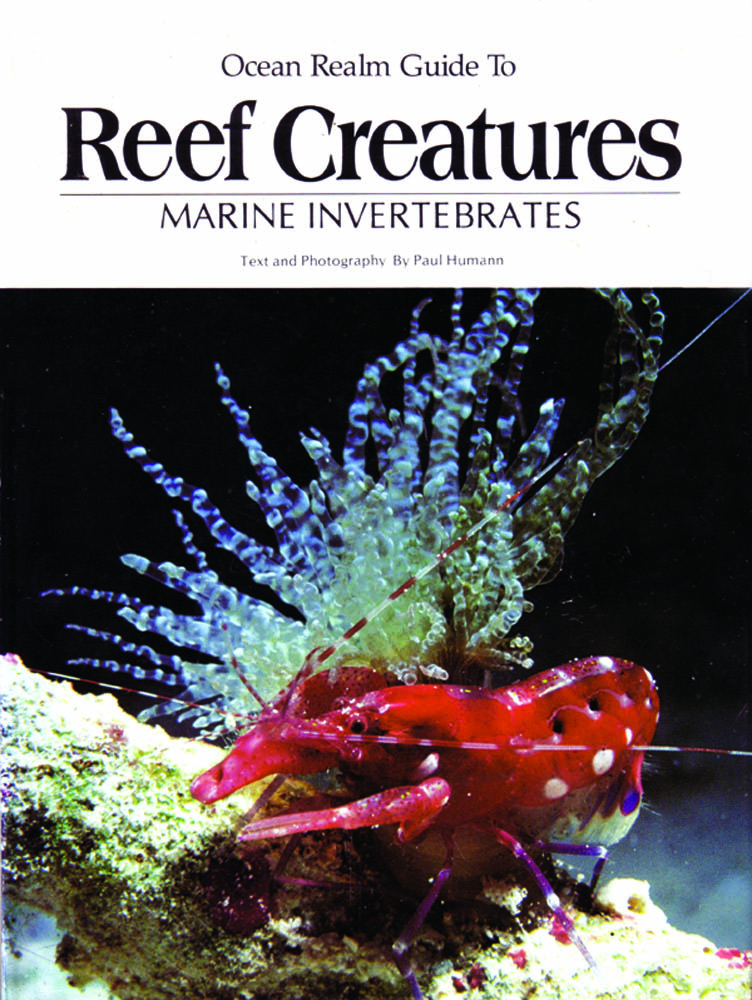

What was your first book?»A small, but large format, pictorial about the Cayman’s underwater vistas. That was in 1979. But poor profits reinforced my thought that selling pretty pictures and coffee table type books was not the way to make a living. The real start was with Reef Creatures, put out by Ocean Realm magazine in 1982. It wasn’t really a guidebook in the sense of the books we are doing today. It was written to teach divers what kind of animal they were observing, not so much which specific one. For example, to teach them the difference between an anemone, zoanthid, corallimorpharian or cerianthid tube dwelling anemone. Others followed?»My first comprehensive identification book was Corals, also put out by Ocean Realm in 1983. Did magazine work also step up?»I was working closely with the Ziff publication Sport Diver and then with Ocean Realm when it started.

I understand that you even hosted Jaws author Peter Benchley for a television special.»Yes, it was an ABC hour-long sports special, The Spirit of Adventure series. I was Peter’s personal guide to see the marine life of the Galapagos Islands and especially the sharks. I had been escorting diving groups to Galapagos for years, and by the time of the special in 1988 had spent cumulatively nearly a years worth of time in the islands. Howard Hall and Stan Waterman were the cinema photographers. The show was quite a hit as I bumped into re-runs for years.

Ocean Realm Magazine

You also got involved in editing Ocean Realm magazine. How did that come about?»Richard Stewart, the founder, sold the magazine in

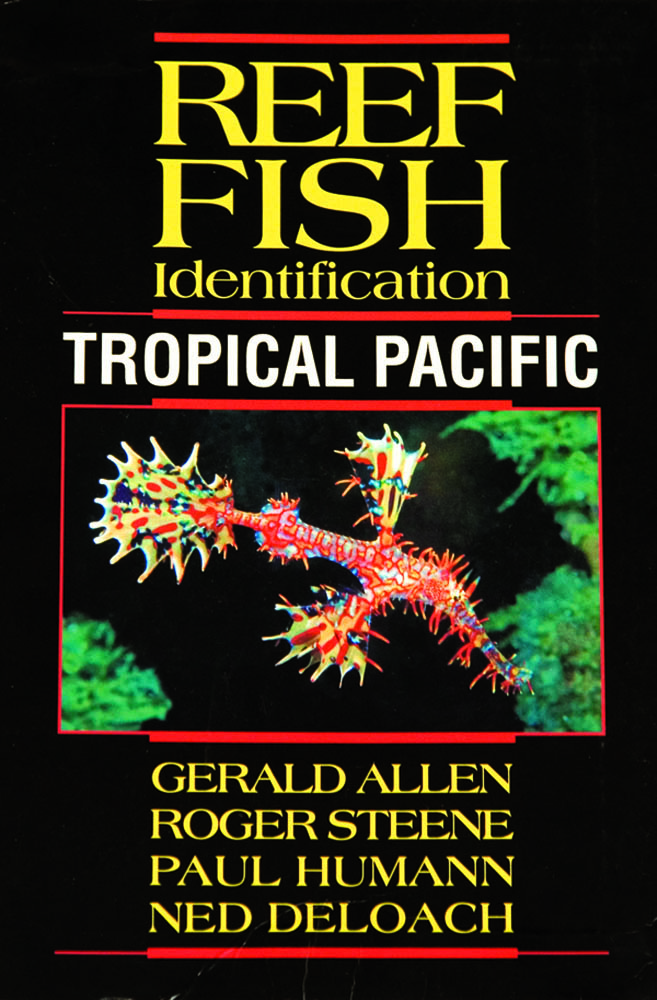

the mid- 1980s. I was interviewed by the new owner, who by twist of fate, hired both Ned DeLoach and me as coeditors. Ned’s claim to fame at the time was his Florida Divers Guide and his close association with the cave diving community. Ned and I had become acquainted several years before through a mutual friend and immediately struck up a strong friendship. You met Ned DeLoach then. Is that what fostered the basis of the New World Publications business?»Indeed, it was our working together at Ocean Realm that made us realize we worked well together and we formulated the idea of a series of guidebooks at that time. Starting a publishing company from scratch in a decidedly niche market like marine life ID books had to be a challenge. What were your first titles and how did you break into the market?»We needed over $100,000 (in 1978 dollars) to put out the first book so we tried to find a partner. First we approached a printer and then a color separator, but both turned out to be less than desirable partners. We were lucky neither worked out. We didn’t want to go to a book publisher because both of us had had bad experiences with other publishers in the past. Besides, we wanted to run the whole show, so we decided to bite the bullet and took a big gamble. We both second-mortgaged our homes to the hilt and lived off of credit cards, hoping to pay everything back within three to five years. Ned was already successfully marketing his Florida Divers Guide directly to dive stores, so they easily agreed to start selling our first Reef Fish Identification book as well. We are a great example of the American Dream come true, because the book was an instant hit and sold like hot cakes. We paid off our second mortgages in only six months! We have run in the black ever since.

How many titles are in the New World library now?»Ten books that we authored and we are working on two more. We also market a number of additional books by other publishers and are starting to publish books by other authors like you and Stan Waterman. Since your books are about the only comprehensive ones out there, how do you get your identifications?»It started back when I was living in Cayman. On a night dive I discovered a fish with glowing light organs under its eyes. Shortly before then I happened to have dinner with Al Giddings and he told me about filming Flashlight fish in the Red Sea. So I thought this was the same thing. One of my passengers told Dr. Bill Smith-Vaniz, a noted ichthyologist, about the sighting. Next thing I knew he was on the phone. It seems the species in the Caribbean was named Kryptophron alfredii, and was known only from a couple of dead specimens collected at over 600 feet way back in the early 1920s. My sighting created quite a stir in the world of ichthyology because they were thought not only to be rare, but also to inhabit only deep depths. Shortly thereafter we were chartered for two weeks by the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences, Scripps Institute of Oceanography, and the California Academy of Sciences to find and collect this little bugger. And, indeed we found and captured the first living specimen at 220 ft. on a night dive. Remember Martini’s Outlaws? No, I don’t dive that deep anymore and no, I don’t think anyone should unless they are on mixed gas – I survived by dumb luck. Ultimately, we found the species as shallow as 40 feet late on moonless nights.

Finding that fish and getting to know the ichthyologists on the subsequent cruise opened the doors of the scientific community to me. Marine taxonomic scientists around the world and I have developed a good rapport. I freely provide them with pictures of living species in situ for their scientific use and they provide me with identifications. Not uncommonly, however, they are unable to make an ID without a specimen. In those situations I go back out, photograph the specimen, and then collect it. Many specimens from this work now reside in the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum’s collection. One cryptic species turned out to be a coral unknown to science. Dr. Stephen Cairns with the Smithsonian named it in my honor, Coenocyathus humanni. Another result of this work is that many of my pictures are the first ever published of living specimens and, in turn, establish visual identification criteria for many marine animals. This allows scientists to take marine life surveys without the need of collecting specimens –a non-impact plus for the marine world.

Collection of Awards and Accomplishments

You’ve also collected a few awards along the way?»In the beginning we sold our books only to dive stores, but realized getting into bookstores was essential to our long-term health as publishers. We quickly found out that bookstores buy almost exclusively from two wholesalers, Ingram and Baker & Taylor. Stores don’t want to deal with small one or two product publishers like us. Problem was neither did the wholesalers. We talked to them numerous times and got nowhere. They almost arrogantly would not give us the time of day and “pooh-poohed” potential sales. Then we heard about a competition run by the American Book Sellers Association in which newly published books can be entered into a number of categories. The winners are published in their trade magazine, which goes to every bookstore in the United States. As a prize for winning you get a free full-page color advertisement in the magazine. We entered the second edition of Reef Fish Identification and won The Benjamin Franklin Award for Best Reference Book published in 1994. All of a sudden we were receiving panicked phone calls from the wholesalers wondering why they were not selling our books as they were getting inundated with orders. Duh! Ingram quickly became by far our largest customer and love us to this day. Then Amazon picked us up, we now receive an award every year as the publisher selling more marine life subject books than anyone else in the world. Not bad for a couple of scuba bums, huh?

What about personal awards?»In May of 2006, I received the United States Coral Reef Task Force award for the advancement of public awareness and education concerning marine life environmental issues. Then in November of 2006, the DEMA Reaching Out Award for my contributions to the advancement of the sport of scuba diving. And in January of 2007, in Grand Cayman, I was inducted into the International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame. Tell us about the process of creating the Reef Environmental Education Foundation?»In researching for our first fish ID book, we realized that the scientific community knew very little about the abundance of most reef fishes at a given location, and to a degree, their geographical range was unknown as well. We thought, “There’s no excuse for that! With so many divers in the water every day, there ought to be a way to put their bottom time to work.” We thought of the successful Audubon bird-counting program and concluded divers could do the same thing for fish. We were very fortunate that both NOAA personnel and the Nature Conservancy bought into the idea early on. With their help and guidance we were able to design a method of taking the surveys that would be fun and interesting for recreational divers and at the same time result in data that would be meaningful and useful to the scientific community.

How far reaching are these collective surveys?» To date, volunteer recreational divers have made over 100,000 surveys of fish species populations throughout the waters of North and Central America, plus Galapagos and Hawaii. It is the largest marine life database in the world. The results of these surveys have been used by marine life scientists and management personnel ranging from NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuary program, to Florida’s Fisheries Management personnel, to the Cayman Islands Dept. of Environment. For example, when Florida’s fishing commission was asked to take Goliath grouper off the endangered list, they went to the REEF database and armed with that information refused the request. REEF is conducting research on the effect of an artificial reef on surrounding marine populations for the State of Florida. The National Marine Sanctuary program uses REEF to assess the effectiveness of “no-take” marine reserves. And the National Park Service is using REEF to inventory fish species in park waters. The Cayman Department of Environment worked with REEF to study Nassau grouper mass-spawning behavior and the effects of fishing them. It’s wonderful to think that thousands of recreational scuba divers are providing this useful scientific information, and at the same time are having one heck of a good time. Like underwater photography, it is an activity that keeps divers active in diving for years.

In spite of your pioneering efforts in liveaboards and their operation that paved the way for all that followed, you’ve had your fair share of frustration over the way some of the industry began to evolve. Let’s start with solo diving. You’ve long been an advocate for qualified divers to be left alone in pursuit of photography or other interests. This led to criticism and outright condemnation from the ultra-conservatives. What’s your take on all this looking back?»It was and remains stupid. I still consider the buddy system to be

Buddy diving sounds good on paper, but in reality it often creates a dangerous situation. To be a truly good buddy, you must be aware of your partner’s situation at all times. Far too often, if not regularly, a buddy’s attention is distracted by the marine life being viewed and the buddy is at least momentarily forgotten. When one is relying on the buddy system for assistance in case of a sudden emergency, this is a formula for disaster! Proponents of the buddy system are simply not facing the reality of what actually happens underwater. I know as an underwater photographer, you cannot concentrate on your picture and keep track of your buddy at the same time. It is impossible. And, as a result, I think every underwater photographer, and more importantly his/her buddy, should be forced to take a solo diving course! No solo diving card, no photography. Two final side notes on this subject. I do believe in the buddy system for beginning divers, up to say 50 dives. However, their buddies ought to be experienced divers, not another beginner. And, I’ve been accused of being an anti-social diver, wanting to be by myself. Nothing could be further from the truth. I love having a diving “companion” to share the adventure. I just don’t want the responsibility of being charged with his or her safety.

First SDI “Solo Diver”

In 1999 you were honored by SDI as the first recipient of a “solo diver” certification when they launched their program. Did you think you’d finally see the day when the practice was accepted?»No, I didn’t. I thought the curmudgeons and attorneys would probably see that it never happened. But, I still have forlorn hope. It seems that change of any kind is met

It’s interesting that these practices all became mainstream within a relatively short time. Is diving a better place now?»In general, yes. What else chaps you in the category of silly diver rules?»One issue that does bother me today is the “don’t touch issue.” Let me say from the onset, I do not advocate touching coral, but some of what is currently taught and advocated is false and a detriment to the dive industry. For example, a single or even a few touches to coral causes absolutely no harm. And certainly one touch does not kill hundreds of polyps and make the colony die as I know numerous instructors have taught their students. Actually coral is tough stuff and quite resilient to damage. Surprising to most people, the primary way new colonies of more fragile branching corals start is from a broken piece. However, at least from an ascetic point of view, contact hard enough to break the coral should definitely be avoided. In an attempt to hold diver contact to a minimum the pendulum has swung to the neo-conservative side. For simplicity, divers are being taught “don’t touch anything; stay at least three to ten feet away from everything!” Even the sand or algae beds. And, blatant falsehoods are being taught to support those rules.

The problem with this approach is that divers do not really get to see a lot. They can’t observe many of the smaller animals or study interesting behaviors. For example, how can you observe the interesting interaction between a shrimp goby and its companion blind shrimp hovering three plus feet above the sand? Or watch the interactions between an eel and cleaner shrimp hovering above the reef? The answer is: you can’t! And, you’ll never see most of the wonderful cryptic animals. By hovering three feet or more above things, you’re missing a majority of the greatest wildlife show on earth! The result is that many new divers quickly get bored with diving and drop out. We have a huge dropout problem in this industry and our approach to “don’t touch” isn’t helping. We need to train people how to touch or rest on the bottom without doing damage and observe responsibly. Regrettably, the powers-that-be seem to think that would be too difficult to do or that the average recreational diver is too dumb to understand and learn what might be harmful and what is not. This is too bad, because in the long run it is divers that are most passionate about preserving the reefs. We need more environmentally concerned divers not less.

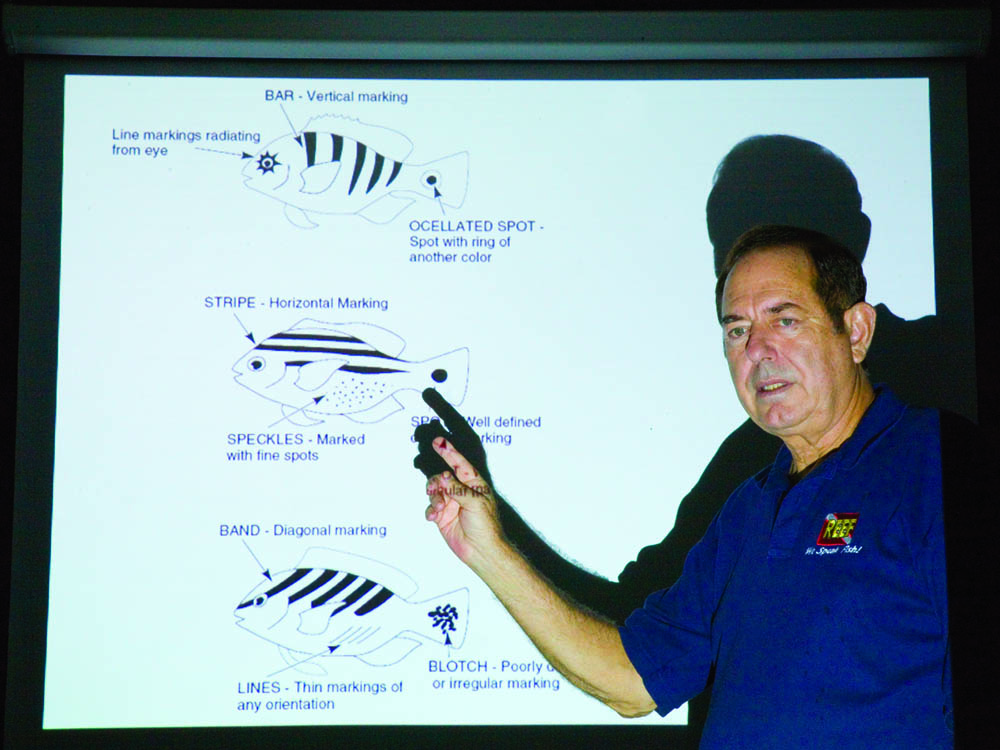

Should the diving industry look to innovation as a growth tool instead of its historical conservatism?»In most cases, probably so. I believe one of the biggest reasons growth of diving as a sport is stagnant, at best, is because the dive industry historically and continues today to ignore the single most positive thing it could do to grow. And perhaps more importantly reduce the notorious dropout rate… said by some to be a disastrous 95 percent within three years of learning to dive! Why do people want to dive in the first place? Asked that question, the vast majority will say, “to see the marine life.” What does the dive industry do to nurture this natural interest? Absolutely nothing! How many times have you been on a dive boat where there is a young couple making their 3rd or 4th dive. They come up from the dive all excited about this wonderful fish they have seen and want to know what it is. They describe it to the dive master — far too often the answer is, “Uumm, I don’t know.” The couple’s excitement is tempered. If this happens many more times the couple will become another dropout statistic. The beginning dive course should include some information about the marine life they are going to encounter and how to enjoy what they are seeing. And the 2nd course should be about marine life, not rescue diver or some other nonsensical specialty that does nothing toward keeping a person interested and involved in the sport. Specialty courses have captured the “merit badge” concept rather than teaching divers how to enjoy the wonders of marine life. I was telling a high-ranking person in one of the training agencies about this. He said, “You may be right Paul, could you develop a fish identification course for us?” “Sure, I’ll start with the Caribbean.” He replied, “Oh no! It has got to be international — something we can teach everywhere. That’s the way all our courses are designed.”

Marine Life on DVD

I fumed quietly and attempted to explain what should have been obvious: “But, you can’t do that; fish and even their families in Australia, West Coast and Caribbean are all different. A single course for all is impossible.” Then, underscoring his ignorance of marine life he responded; “Oh I’ll bet I can, I’ll work on it.” Needless to say he could not, so the whole idea of developing some courses about marine life was dropped. The dive training agencies would be the logical organizations to develop and market such courses. However, in general, they have developed nothing meaningful. Consequently, Ned, his video photographer wife Anna, and I have given up. We are currently in the process of developing our own DVD about marine life for beginning divers that hopefully will make their first dives a more meaningful and enjoyable experience. With luck this will be the first of many to come. REEF is also developing the first of several dive store supervised home study fish, identification courses on DVD.

Finally, you have the benefit of 45 years perspective diving in the Caribbean. There have been some devastating changes to the marine environment over that four-decade span. One recent study released their results and noted that nearly 80 percent of the coral in most parts of the region are dead or dying. Is there any hope for the Caribbean?»I think the 80 percent in most parts is wrong – a few parts would be more accurate at this time. Nonetheless, there is no question that hard corals are in decline throughout the region and I don’t see any reason this will not continue. It is only a matter of how fast. I think most hard corals will be gone in a matter of 10-30 years as a result of global warming. The full impact of this is not clearly understood at this point, but it is certainly a cause for serious concern.

If you put a diver in sat with the hatch depth around 400 feet, it still gives him the excursion capability to go below that to what, another couple hundred feet or so with no decompression and return to storage?»You can always cut your pressure in half without decompressing. So if you’re stored at 400 feet, you can go to 800 feet. It depends on the logistics of support. You know, do they have a bell that will go that deep? Are the cables set up properly? Does the job require that many hours? Then there’s the safety factor. So instead of storing the guys at 400 and making 800-ft. runs, the companies prefer to store the guys a little deeper so you don’t have any chance of getting the bends.

Your company gained a tremendous reputation early on with your lightweight divers’ helmets. What other products are you making to support this? Are you actually designing suits and bells, things like this?»No. We work with the suit manufacturers to marry the suits to the helmets, but we don’t actually build the suits themselves. We build a few scuba-diving suits since we’re going to have a neoprene department anyway, but no, we stick mainly to helmets and avoid chambers and plumbing and stuff like that.

The Caribbean is not the only region to be severely impacted. Palau and Fiji have been particularly hit by influences that affected stony and soft corals. This phenomenon can be timed coincidentally with the 1997-98 El Niño. Are even these remote areas to be gradually eroded simply due to natural impacts?»Unquestionably global warming is the primary culprit. Anyone who questions the reality of global warming has their head in the sand. Stony corals around the world will be impacted, and again, I think most corals will be gone within the next 10-30 years. We are lucky to have seen them; our children will not be so lucky. It’s interesting that you included soft corals, my impression visiting Fiji two years after the most serious bleaching event, was that the soft corals were more plentiful and vibrant than ever, and abounded in areas of dead stony coral.

My impression was based on direct observation of soft corals following the El Niño in both areas. In some cases, the soft corals just simply disappeared. I compared it to photos I had taken in earlier years. It was like they had been “Photo-Shopped” right out of the images. Do you think there is any hope at all?»I see two rays of hope. Perhaps the American public will be smart enough in 2008 to elect people that understand the seriousness of the problem and will do something about it, including changing the American peoples’ mindset about how we live. Do you drive a SUV? I 1. Paul and publishing partner Ned Deloach 2. Fish ID lecutre, 2004 3. Sylvia Earle, Eugenie Clark, Humann and Deborah Danner, 2005 don’t! And, perhaps evolution will play a role. Darwin was right; I’ve seen underwater some examples of what is probably “survival of the fittest” in action. After the severe bleaching event in Fiji, I swam over a huge area of dead tabletop corals, but to my surprise for every 15 or so dead ones there was a living thriving colony. Were these genetically superior colonies that were able to withstand the warm water temperatures? Will they spawn to produce less vulnerable colonies? Let’s hope so.

In closing, where is the best diving in the world today and why?»Oh, that’s an unanswerable question. Every dive destination has its unique charm and I love them all. However, as a final note, I would like to say that I hope my books and photographs inspire people. Divers are fundamentally explorers. We want to go where few people have gone… to discover places that most people only dream of, or only read about from their armchairs. If my life’s work has contributed anything to the dive community, I hope it is to inspire people to explore, discover, enjoy, and, ultimately, to preserve marine life.