ANTARCTICA

The deep south

Article by Laurent Stampfli

Antarctica lies at the far southern edge of the planet, a place that is visible no matter which way you look at a globe. However, it remains the most inaccessible location on our planet. A white continent, full of mysteries and wonders that we usually discover only through documentaries and explorers’ tales. A land coveted for centuries, but protected and regulated only quite recently.

For more than 10 years I have dreamt of going there. I have analyzed the options, studied the routes, considered alternatives and hesitated again and again. This time the opportunity is simply too good to miss. A casual announcement, a successful first contact and an almost immediate commitment later, and I am off on this crazy adventure in the company of three friends from our club “1001 Plongées”.

54°48.4’ S / 68°17.6’ W: Ushuaia

The gateway to the northern part of the Antarctic continent. “Only” 1,000 km separate it from the peninsula, across the famous Drake Passage.

A small town whose main activity seems to be focused either on outdoor pursuits, with Patagonia as a fantastic playground, or on chartering boats. Cruise ships, expedition vessels, ocean-going yachts, fishing boats, there is something for every taste but in the end these travelers are all captivated by a single destination: the entrance to the White Continent.

Another activity is slowly developing diving in the Beagle Channel. After so many hours of flying, I am delighted to finally strap on my fins and discover the local waters. A small, very friendly dive center, Beagle Buceos, takes us out along the coast for two dives. It is run “American style”, with two consecutive dives at the start of the day and a return to port early in the afternoon.

My first dive south of the American continent, the southernmost dive of my life so far. The Beagle Channel is an arm of the sea, so it is salty, with marine life similar to that of the coast. A current, which I imagine is tide driven, stirs up the bottom, clouds the visibility and creates a clearly noticeable swell. Kelp forests, juvenile spider crabs, Antarctic cod, other cod species, sea stars of all kinds including the famous long-armed sun stars. All of it in brownish water at 9°C, still warm compared with what is waiting for me farther south. It is possible to see seals and sometimes penguins there depending on the sites and the season, but I was not that lucky this time.

On 11 February I am at the port, the departure point for a 28-day odyssey with around 160 other people, including 75 passengers, 24 divers and about 60 crew members.

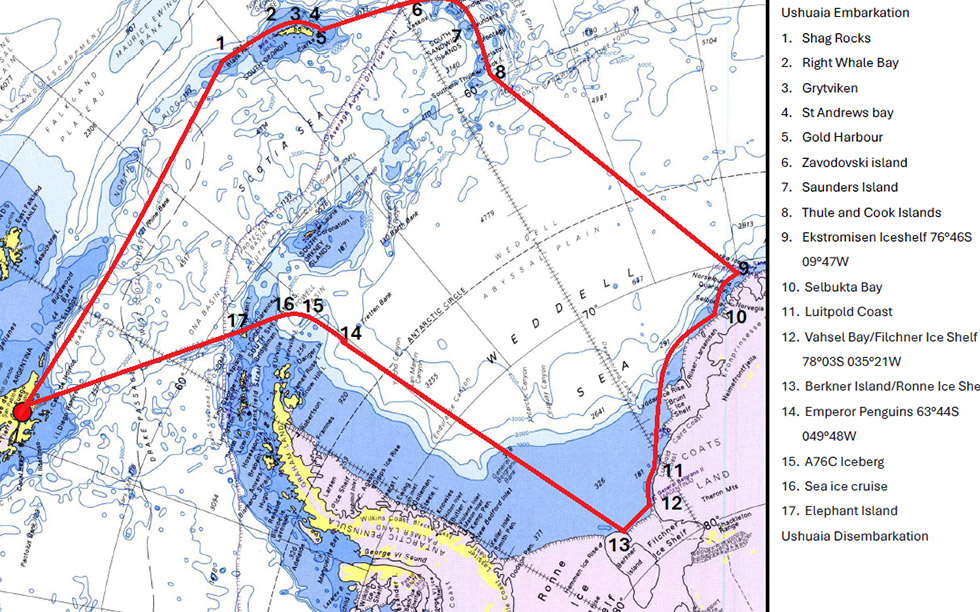

Our ship, the ORTELIUS, is ice strengthened and ready to sail. For this expedition it is exceptionally equipped with 10 Zodiacs and 3 helicopters. The common thread of our journey will be Sir Ernest Shackleton’s legendary Endurance expedition, whose trail we will follow for a good part of the voyage.

The objectives are varied and numerous: scientific teams, film crews, wildlife photographers, polar enthusiasts, former polar base staff, carefully selected divers and ordinary tourists of the extreme. All these passions come together in a single group aboard this truly unusual expedition. It is the first time that such an itinerary has been approved by the IAATO, the umbrella body for activities in Antarctica, so it is a first in many ways. That is why the lucky ones selected are experienced polar enthusiasts, and I am fortunate indeed to find myself among them.

Once the ship’s crew and expedition staff have introduced themselves, and the briefings and safety drills are done, we finally weigh anchor. Under grey skies that herald a rough sea, we leave the Beagle Channel and enter the famous Drake Passage, fortunately heading east with the current behind us which helps to soften the swell.

53°51.6’ S / 38°42.5’ W – The Islands

Our first waypoints are the South Georgia Islands followed by the volcanic chain of the South Sandwich Islands. Although they take us off the direct line to our destination, the passage through these islands is essential if we are to fully appreciate the local wildlife (and plant life, even if it is sparse). It is also an opportunity to have our passports stamped with the last “British” seal of the South Georgia Territories, a point of pride for any traveler.

These wild, remote islands are home to colonies of hundreds of thousands, even millions of penguins. Seals, elephant seals, albatrosses, petrels, all of these species that usually feel so distant appear in their thousands before our eyes, going about their simple lives while we, mere visitors, are just passing through and are curiosities for these animals that are neither very shy nor very fearful.

The regulations require us to keep a good distance, however, because avian flu has recently spread to these islands and it is a scourge that could gradually wipe out the local bird populations. Similarly, extremely strict biosecurity and disinfection procedures are imposed every time we disembark and re-embark on the ship in order to avoid introducing alien species onto these lands. In the past, whaling activities inflicted huge damage on local species by deliberately or accidentally bringing in rats, rabbits, goats or even deer, which reproduced unchecked and threatened native populations. Since then, a massive eradication and restoration effort has been carried out by various agencies to protect these islands and restore the balance.

We complete our check dive here, this time in real conditions. Along the steep cliffs of these legendary islands, whose names date back to the great expeditions at the beginning of the last century. Right Whale Bay, Gold Harbor in South Georgia, then Thule Island in the South Sandwich Islands, where we are among the first to ever dive in these almost unknown waters. The water temperature drops from 2°C, to 1°C, to 0.1°C, cooling with every step we take farther south. Underwater, the flora and fauna resemble those of the Beagle Channel, but wolffish and seals now gradually replace the crabs and new species appear that we struggle to name. This is of particular interest to the scientists, who encourage us to photograph them so they can be identified later by the specialist community. It seems that during each previous survey, new species have been discovered. It shows just how much we are entering an environment that is still little known and seldom studied.

66°33.4’ S / 17°47.7’ W – Crossing the Antarctic Circle

Day 11, 21 February at 10:30, we cross the invisible yet symbolic line of the Antarctic Circle. This time we truly are in the far south of the globe, far from all civilization. Our satellite screen shows only a single fishing vessel somewhere in the entire Weddell Sea. We are completely isolated, with only a few remaining albatrosses taking advantage of wind gusts around the ship and whales that surface regularly all around us for company.

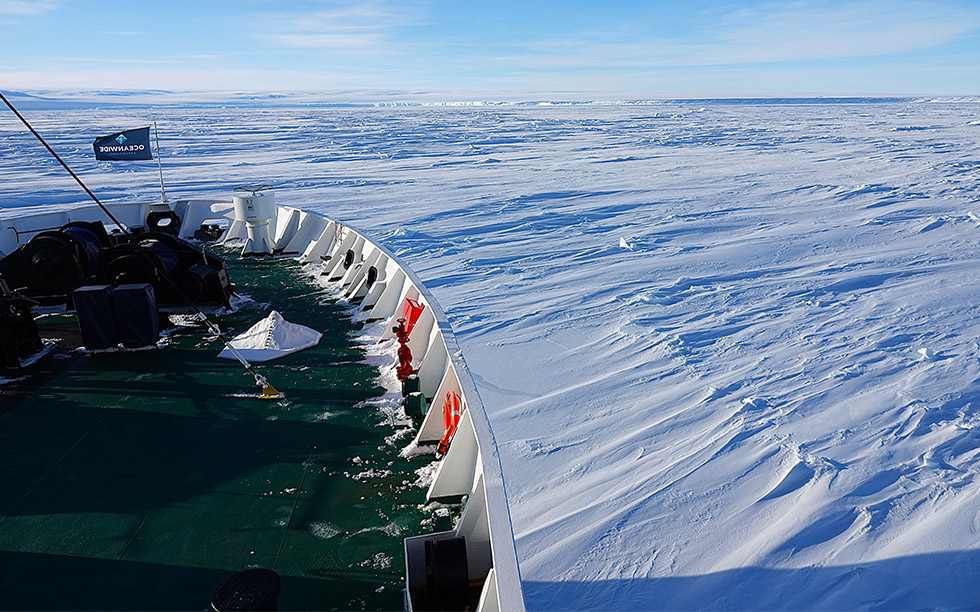

We continue straight south, keeping a careful eye on the icebergs, which are increasing in both size and number. We are very fortunate with the weather and with a very skilled crew that plays the weather windows to perfection in order to give us the calmest possible passage, much to our stomachs’ relief. Most passengers use seasickness patches as a preventive measure so that they can stay fit for their activities. Even the most experienced travelers can suffer from seasickness.

71°27.0’ S / 12°42.2’ W – Coast of the Antarctic Continent

Day 13, 23 February, we finally reach land, or more accurately the ice shelf off the land itself. As everyone knows, Antarctica has on average 2 km of ice covering its entire surface, which is equivalent to the combined area of the United States and Mexico. Its imposing coastline of sea ice forms every winter and then breaks up into giant icebergs in spring. These are carried away by the circumpolar currents. This freeze and thaw cycle is vital to the proper functioning of the major ocean currents and everything that depends on them, including the regulation of global temperature and the survival of many species.

We are now facing this gigantic mass of ice called Neuschwabenland, appearing at times as vast plateaus and at others as compact blocks of ice in all sorts of shapes. Aboard our ship, which now feels very small, I feel tiny in the middle of this frozen immensity.

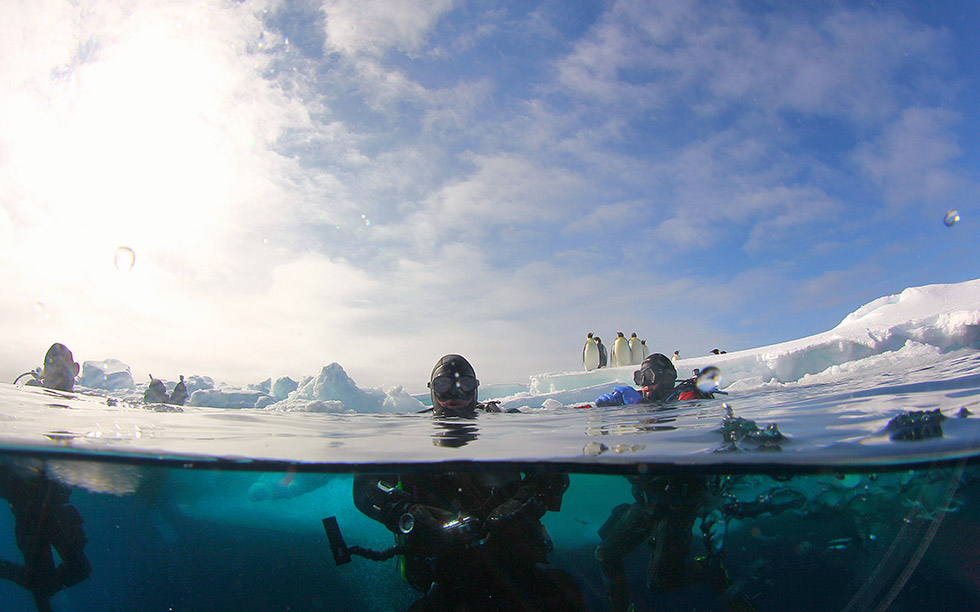

Thankfully, emperor penguins, leopard seals and various seabirds are there to remind us that this environment is their natural habitat.

After a first helicopter foray to fly across the pack ice and reach the actual continent (still under ice) about five kilometers away, we make our first dive around an iceberg in order to acclimatize to this new extreme environment. The water temperature is –1.8°C, right at the freezing point for seawater. The air temperature is about –10°C at the time of entry, and the bottom is beyond our sounding range. Polar diving procedures have to be followed very carefully this time.

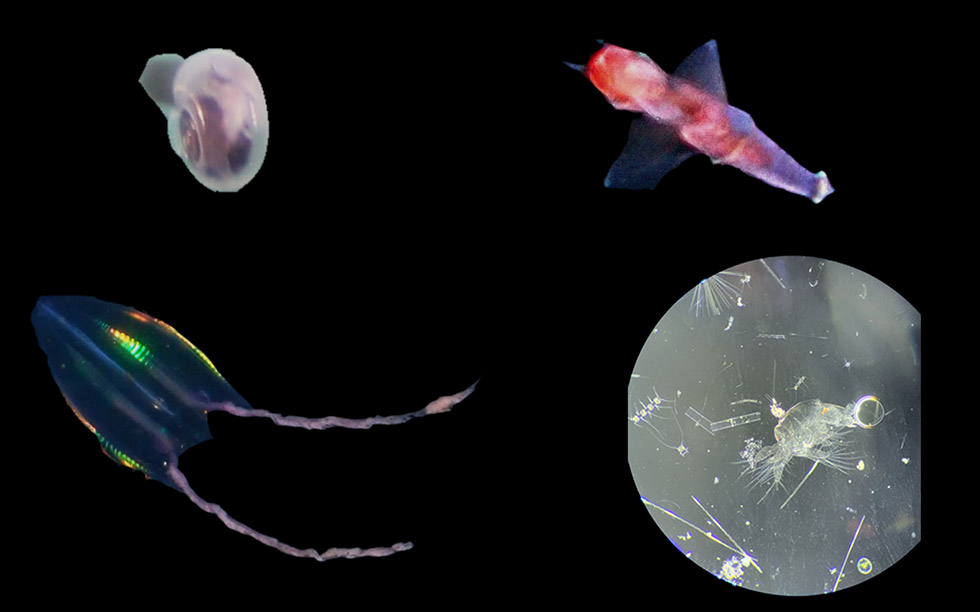

The water is dense, green and full of plankton of every kind. The sheer variety and quantity are astonishing. We encounter both zooplankton and phytoplankton such as sea angels, sea butterflies, pteropods, salps and more. Later, water samples examined under the microscope reveal species invisible to the naked eye, like copepods, diatoms and dinoflagellates, a real primordial soup in a frozen world. Better not swallow any of it.

As you can imagine, plankton soon became one of the most fascinating topics of the trip and everyone got involved, guided by the world-renowned researchers studying it on board. I think I caught a glimpse of an icefish larva and tried to photograph it, but by the time I had managed to work the camera with my numb fingers, it was gone. No photo, no proof. That was the rule.

78°03.5206’ S / 36°03.5413’ W – A Record (?)

Day 16, 26 February, we have been sailing for several days in true expedition mode, off any pre-planned route, adjusting course on sight according to the whims of the ice and the weather. The expedition leaders and bridge officers, after carefully studying the conditions, spot a unique opportunity. These favorable conditions, plus a bit of luck, allow us to slip through an opening in the pack ice where the ocean is usually completely frozen over.

This gives us the chance to bring the ship into Vahsel Bay, a place normally inaccessible by boat, in front of the Luitpold Coast between the Lerchenfeld and Schweitzer Glaciers. A promising name for Swiss divers. It is a new record for the ship, probably the first passenger vessel ever to reach such southerly coordinates. For the divers, it is the promise of an exceptional dive and we hurry to kit up so we can be part of it.

An abyssal bottom, pack ice stretching to the horizon, open water with current, the conditions are far from ideal, but I cannot pass up this chance. We decide to dive beneath the Zodiacs along downlines to avoid being swept under the ice. Several times we have to reposition the Zodiacs because the current is carrying us away. Underwater the temperature is still –2°C. Visibility is somewhat clouded by plankton and there is nothing truly remarkable to see, but the moment feels unique and I end up spending nearly 40 minutes enjoying this extraordinary dive. A few photos to immortalize the moment and it is already time to get back on board because the ocean is starting to freeze again and the ship needs to free itself from there.

To celebrate this exceptional dive, the Swiss dive team go all in. A fondue, brought specially from Switzerland, is improvised on deck. A real challenge, because the cold freezes the gas in the burners and even the white wine and pickles. It is –18°C and the sky is ablaze with a magnificent sunset that closes this day of records in style.

Heading North Again: Questions…

Since the pack ice drifts according to wind and currents, one question hangs over this historic foray into Vahsel Bay. Is it really a record, or is it actually a troubling sign of changing climatic conditions?

A record, certainly, because we have reached and dived at coordinates in the Weddell Sea that until now were never attained by boat. We are seven days of sailing from the nearest possible rescue, which really brings home the scale of this journey, the level of risk acceptance and the potential consequences of even a minor incident.

At the same time this record would not have been possible in the past, simply because the pack ice blocked access. Was it just good luck, or should we be asking whether global warming is disrupting the normal operation of the planet’s refrigerator? Many scientific observations show that changes in water temperature in these regions, together with the frequent discovery of new species, point to a rapid shift in response to a changing ecosystem.

Concepts that are too complex for a non-specialist like me, yet they still make me question things.

As we pass over the site where the Endurance sank, rediscovered only recently at a depth of 3,000 meters, we pay tribute to Shackleton’s expedition and think about what those brave men endured for months in the cold and solitude of such hostile environments.

Luxury Tourism or a Real Expedition?

Back home, several weeks after the end of the trip, my thoughts keep taking me back to this extraordinary journey. Through the porthole I still see the endless procession of icebergs. From the deck I picture the blows of whales as they surface. On land or up on the ice floes, I remember the penguins (yes, penguins) stretching as far as the eye can see, waddling along while screeching, and the young seals chasing me like playful puppies. Finally, under the frozen surface, I recall dives that were sometimes crystal clear, sometimes full of plankton. So many things that had become almost everyday and routine, but which in reality are completely out of the ordinary.

Was it worth it? Some critical points were raised during the trip.

These adventures, for example, help raise awareness and educate people about the ecosystem and about Antarctic tourism. Such briefings are mandatory for any voyage in these regions.

They also encourage the presence of direct witnesses who help monitor and report illegal krill fishing, which is the main threat in these waters. Krill plays a key role in regulating plankton, the planet’s primary lung.

In addition, these expeditions, led by scientists, help to improve our knowledge of this fragile environment and highlight the importance of protecting it.

Being confronted with all of this can help people grasp what is at stake and become ambassadors for Antarctica, sharing this knowledge with others.

Everyone is free to form their own opinion on the matter. Diving by its very nature is not a very eco-friendly activity, but the images and messages it carries help explain why more and more people take it up and become more aware of the marine environment. I believe that is a positive thing.

About the author – Laurent Stampfli

Diver since 2012

TDI Instructor

Cave, TMX (trimix) and CCR diver

留下回覆

想加入討論?隨時歡迎參與討論!